Veterinary group advocating for industry refinements.

Three Murdoch veterinary alumni, accompanied by another seasoned veterinarian and three trusted associates from varied professional domains, have united to launch a pioneering social enterprise. Their mission? To bring additional support to a sector of pet owners and potentially beneficial organisational enhancements to veterinary practices across Australia.

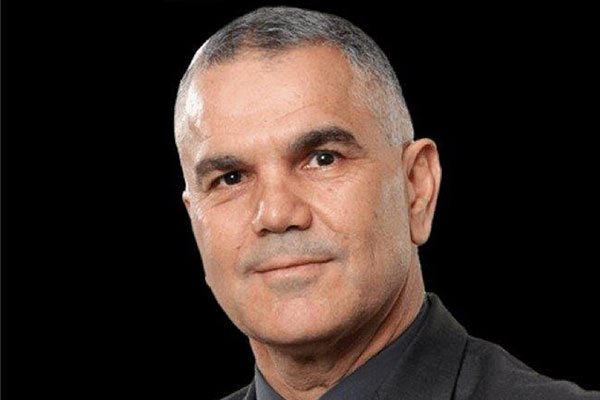

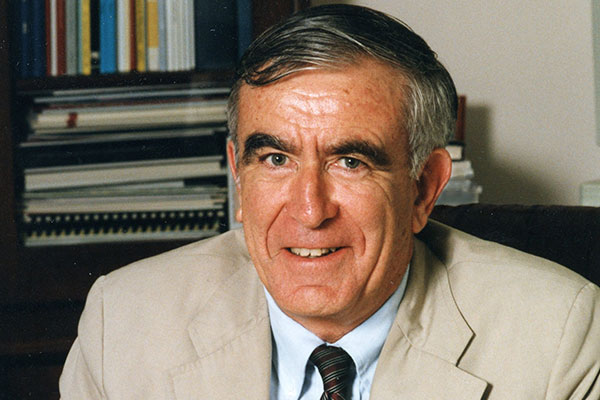

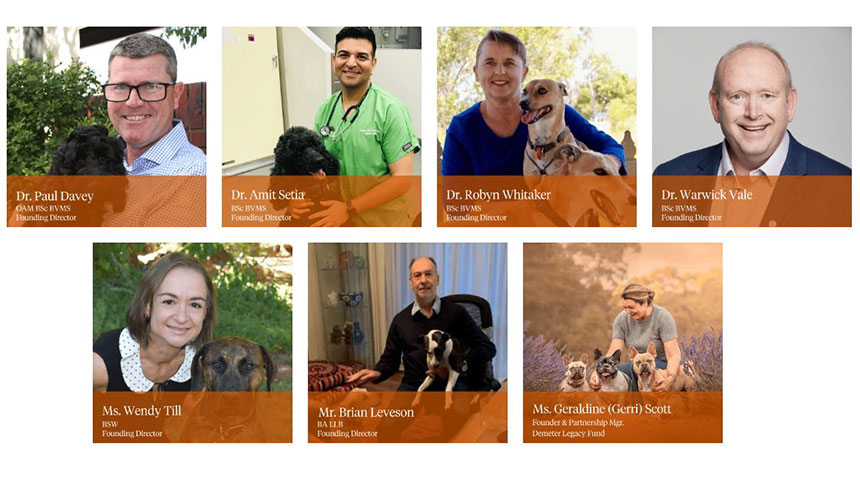

Dr Paul Davey (BVMS 1992), Dr Robyn Whitaker (BVMS 1989), Dr Warwick Vale (BVMS 1989), Dr Amit Setia, Ms Wendy Till, Mr Brian Leveson, and Ms Geraldine (Gerri) Scott, formed a social enterprise realising from their many years of professional experience, that there were some significant gaps in the veterinary world that they could help address.

“We all ended up overlapping in various ways, with some common goals and desires to do things in the veterinary and animal care space. Initially we came at it from slightly different angles, but with some very common threads, and ultimately, our organisation, Veterinary and Community Care (VaCC), evolved with a focus on the mental health for all of those involved in caring for companion animals,” said Dr Whitaker.

The non-vets in the endeavour are Wendy Till, a social worker and potentially the only veterinary social worker currently in Australia, and Brian Leveson, a senior government lawyer. Completing the organisation is founding benefactor and committee member Gerri Scott, who is also a strong supporter of the enterprise through her Demeter Legacy Fund. The work the team do is 100% voluntary, with all work conducted around and in addition to the members’ full-time positions.

Key to the enterprise is the focus on community centred veterinary care. Essentially, the difference compared with traditional veterinary care is an increased focus on the individual situations of pet owners. The people who are the caretakers of the animals are looked at as a very integral part of any care program.

“Traditional veterinary practice is very animal focused. It is focused on what is the best outcome for the animal. As it should be. But the animals come with people. And the people play a very large influencing role on the care of the animal as they all come with their own set of circumstances which can affect the animal in a variety of ways,” said Dr Whitaker.

As a result, VaCC advocate for the practice of “contextualised care” where the care looks holistically across the animal and the owner with a significant focus on the clientele who may be facing vulnerabilities and disadvantage. It’s not exclusive to that, as community centred practice can go across every spectrum, but as a rule, it has a focus on the cohort of animal carers that need additional support. An added layer of help, guidance around decision making, and a plan that can encompass managing financial constraints when needed.

As part of a suite of programs, VaCC do provide a service through Perth Street Vets that services the homeless or those at risk of homelessness. So, what about those who are elderly, facing disadvantage, or living with a disability? VaCC’s sister organisation in Geelong, Victoria (Cherished Pets – also founded by a Murdoch Alumni, Dr Alicia Kennedy BVMS 1986), have a team that includes social workers and community veterinary nurses who can go out to peoples’ homes to assist with treatment programs. VaCC has a goal to provide similar services here in Western Australia.

Central to the main ethos of VaCC, is the promotion of the benefits of developing the emerging profession of veterinary social workers. It is a position in which the USA is ahead of the field. But what exactly do they do?

“The model is social workers, qualified and experienced social workers, who wish to add another professional development credential to their skill set. It’s a training program we are developing where they can ultimately become recognised as a veterinary social worker,” said Dr Whitaker.

Veterinary social workers can offer services across a whole spectrum. On the client side for example, they have the knowledge and experience to proactively look after the client, know what additional services may be needed, know which specialists should be involved, and connect with other agencies or health services required. If a client is facing mental health challenges for example, they can support them through their interactions with the veterinary practice and through the resulting follow up care and treatment program.

“As you can imagine this gives indirect support to the veterinary team. Because every day veterinary nurses, support staff and admin staff are trying because of the force of circumstances, to be social workers when they are not. They are not trained, not experienced, and not resourced. Let’s get social workers to do what they are good at, and provide them with additional information, an extra layer of understanding of the human-animal bond, “said Dr Whitaker.

Ideally, the VaCC team see the veterinary social worker as a resource embedded within a veterinary practice. This is the model primarily adopted in the USA. In addition to the support they provide the client, the social workers can aid the veterinary team with their emotional and mental health management and help to address some of the stresses that come with the profession.

“As a profession we are not very good at boundary setting, debriefing and sharing the mental load that goes with just daily practice,” said Dr Whitaker.

“The rate of attrition of vets out of the profession is a huge problem. Veterinary social workers can help with the most difficult part of being a vet which is supporting the human clients. It’s a fact that the average veterinarian became a vet because they love animals and often, they didn’t appreciate that 80% of the job is dealing with people. And understandably, the vast majority of people that we deal with are often stressed, vulnerable, anxious, upset, or angry,” added Dr Davey.

“As I mentioned, the client management side is probably the toughest element, but it’s also the rollercoaster element of each day, where for example, you may perform a euthanasia, then five minutes later you are in a joyful new puppy consultation, then you are in surgery handling an animal who may be dying under anaesthesia, and so on,” said Dr Whitaker.

The veterinary life is consistently listed in top ten lists for most stressful professions. Dr Davey believes some of the statistics in this area can tend to be exaggerated for the demands of media stories, and due to a lack of accurate data collection, but that there are evident significant stressors within the field.

“One of the statistics referred to when discussing veterinarian stress is that we deal with death 17 times more often than say a GP or a doctor. The death of the animal is obviously a primary stressor, but client management and handling the way the clients are dealing with the death is actually more stressful and traditionally more difficult for vets to deal with. And the essential counselling and empathy and human management is being done in a service climate of back-to-back appointments and long hours and shift work and night calls etc.

“Veterinary nurses and other practice staff do help with grief counselling and client management, but having a veterinary social worker who is able to come in and deal with the most difficult parts of the role will make it a far more pleasant working environment and help make it both a more sustainable workplace and sustainable career pathway,” concluded Dr Davey.

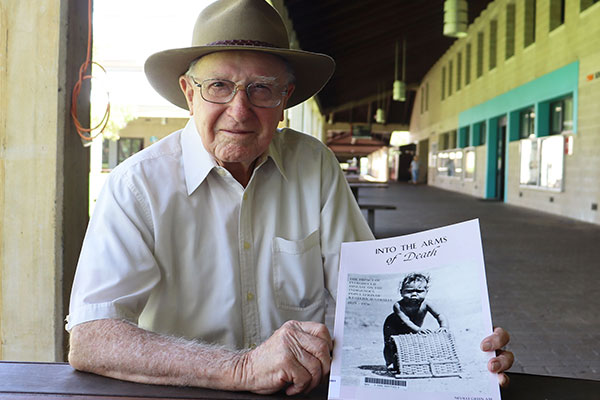

To assist veterinary practices, Wendy Till has created a veterinary social work handbook. The text contains information and resources from the world of social work that a vet practice can refer to for guidance. A first stop, entry level manual that can guide practices on steps to follow, checklists and protocols and the wide range of resources available.

The next level of care up would be implementation of veterinary social workers who can be reached by telephone for advice and guidance, or possibly when practical, visit a practice to aide with a client visit.

But the ultimate goal is the emergence of veterinary social workers as an integral part of veterinary teams. In the United States this goal is already driving change in the tertiary sector. At the University of Tennessee for example, the Centre for Veterinary Social Work is a collaboration between their social work school and their veterinary school. The collaborative program exposes the vet undergraduates to some aspect of social work, and they’re exposing the social work undergraduates to some aspects of veterinary work. Yes, the graduates are ultimately heading for different professions, but it gives them a lens, additional awareness and skills to take forward into their respective vocations.

The Veterinary and Community Care charity has a clear vision of the ways the industry can improve and, in many ways, begin to mirror the field of human health and medicine which already utilises many of the concepts raised - debriefing, utilising external consultants, team management and welfare checks, and looking outside the traditional confines of the sector in order to innovate and enhance quality for the human components of veterinary practice. It is early days, but with funding and support from the private and Government sector, combined with their extensive professional experience and insights, it is evident the team are helping drive a much-needed new path within the veterinary landscape.