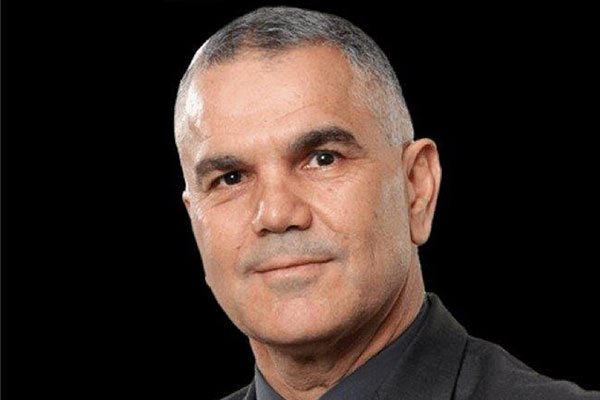

A humble man from the Kimberley who's transformed businesses, lives, and regions and helped protect vast areas of our state.

What was your childhood like?

My early childhood memories are with my family, my grandmother and grandfather along the Fitzroy River; hunting, fishing, catching barramundi, and going to saltwater country from my grandfather’s side, Beagle Bay. So Nyul Nyul and Nyigina and they were days that I understood about sharing because we would always catch more fish than we needed. We would hand out the extras to other family members, either down in the reserve or around town in Derby.

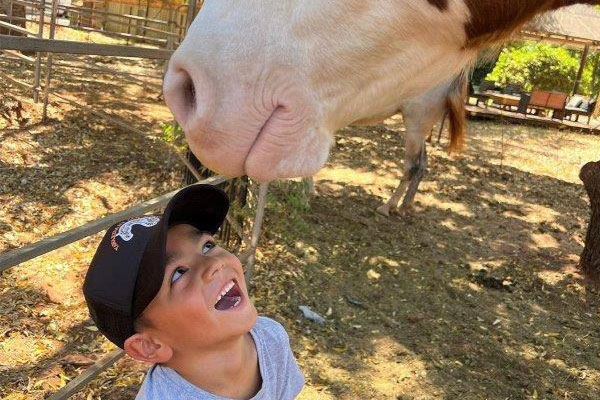

So, I've got beautiful, early memories as a child. When I look back on it, you want any kid, especially your own, to have that same experience of having that connection to the Fitzroy River, to the Mardowarra. It's a place where I think you can heal.

Growing up, what did you learn from your grandparents?

In my early days I spent a lot of time with my grandparents, with Nana, and Uncle Cyril, my mother’s brother. We were always going out hunting and fishing. I missed school, it seemed to be okay to miss school. I never really thought education was important, I was just having fun. It wasn’t until later in life when my father came on the scene that I stayed home more,

Those early days sadly, when I was around six or seven, were ones full of domestic violence. You’ve got to have a stable family to bring up resilient kids and in the early days, until my dad came along, that wasn’t there. So that’s why I spent more time with my grandparents.

What was your time at Murdoch like?

Murdoch was a really important time in my life. I had support from the Kimberley Aboriginal Law and Culture Centre in Fitzroy Crossing, where I worked with a lot of first contact, senior Aboriginal people. They decided to support me to go and study law because they wanted more young Aboriginal people to learn both ways - the white fella law and the black fella law.

Murdoch was part of an Aboriginal pre-law programme, and my scores were enough to get an offer to go straight into Murdoch’s Law school. It was very challenging because my literacy was very poor. It was really like starting school all over again. So, the support I got from Murdoch’s Aboriginal Centre - Kulbardi, the tutoring, and how it was all structured, was fundamental in me being able to take those steps.

It taught me to not look at the destination, but to enjoy the journey, because I never once thought about becoming a lawyer, or that I would get a law degree. I would just be organised and chip away at all my assignments, get prepared for exams and then at the end of the year go, ‘Oh, I made it’. When I did think about the destination, it became overwhelming. So that was my coping mechanism, together with that broader network of students that worked with you and supported you.

It was a great little community. I was a mature-aged student. I had my first daughter, Sara, born while I was studying, and it was a great time. Towards the end of my degree, I had my son, Jared. So both born while I was a student. My youngest daughter was born just as I finished and went back to the Kimberley.

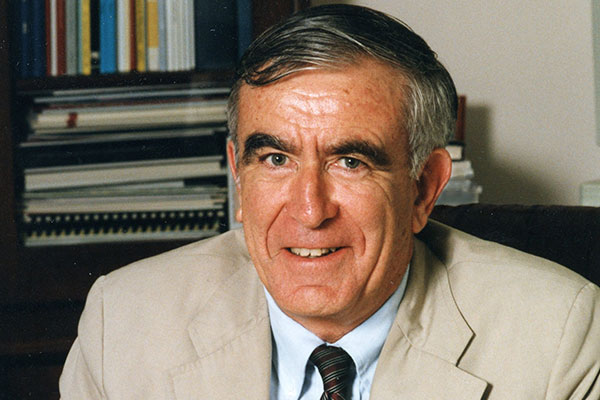

After getting your law degree you went to work with QC and former Fraser Minister, Ian Viner. What did you learn from him?

Leaving university and starting in the workforce was the next big challenge. We were on the edge of changing attitudes about providing equity or opportunities for Aboriginal people. Although we were discussing it publicly as a society, I don’t think we were implementing it very well because I made applications to numerous government departments, big mining companies, law firms, and legal professions and got knocked back.

Ian Viner came about through Pat Dodson. I rang Pat and I said ‘Look I haven’t got any articles. Do you know anyone?’ He sorted me out and I went to chambers with Ian. It was the best time.

He taught me so much. It was not about volume; it was about quality. We would have little pep talks on the way to court because I read with him. I supported him and prepared some of his briefs for trial. It was always about finding the weakest part of an argument and severing it at the joints. I remember he said, ‘You can save a lot of time when you can see these weak links and you can do well for your clients.’ It was a really important time for me. I also learned that working in chambers was a different culture. It was about etiquette. It was about how you treat people. Ian Viner was a great person to work with because he was responsible for a lot of things in Aboriginal affairs when he was a minister at the Commonwealth level.

“Our senior Aboriginal people had a vision to create independent Aboriginal economic development. From the early days, I have committed my time to realising this vision.”

How difficult has it been to stay on course with this vision?

When I finished in private practice in Perth, I went back to the Kimberley Land Council. I was very fortunate to be appointed CEO, because I was just 32. I was one of the younger CEOs of a Land Council. I had no management experience. I walked into one of the biggest challenges of my life and Native Title was almost a dirty word in those days. A lot of advice from people was ‘Don’t practice in Native Title because your career won’t go anywhere.’ Obviously, I didn’t listen to that. I thought Native Title was a magic box because there were so many things you could do, and you could make a positive impact.

The biggest positive impact was creating the Kimberley Ranger Network and that was created out of a combination of political necessity, because you had to manage all your litigation against the State and Commonwealth to recognise Native Title, but you couldn’t work with 30 different Native Title groups all at the same time. You can only afford to really work with two to four Native Title groups to do any real work.

What are some of your proudest achievements from your time at the Kimberley Land Council?

The Kimberley Ranger Network became really important because it provided a basis for getting young people on country to work with senior people, to pass on knowledge, to provide culturally based land management practices, and to document stories and pass on knowledge.

It was also the tool which brought Aboriginal groups together. It’s the most successful employment and training programme and it has grown enormously. I think there are something like 180 Rangers now employed in the Kimberley. Pretty much every Native Title group has a ranger programme and it’s really delivering environmental values for all Australians and the world.

Negotiating partnerships with resource companies while aiming to maximise benefits, economic, cultural and environmental to local Aboriginal people appears incredibly complex. How do you manage to do it time and again?

One of the roles of the Land Council was to provide agreement making functions, and so the Native Title system sets up a representative body as a tollgate.

Every mining company has to go through the tollgate to make sure they complete heritage surveys. They have an agreement with local traditional owners about exploration and ensuring that they don’t damage any Aboriginal heritage sites. And if they find a resource, they negotiate an Impact Benefits Agreement that leaves the community in a better position. As I like to think in pictures, and structure, and systems, we created Kimberley benchmarks.

We were able to make sure and ramp-up each time we negotiated, what we call ‘Best Practice’:

- What’s the best way you can employ and train Aboriginal people? – (Put that in the agreement.)

- What are the best commercial sharing agreements?

- What’s the best way in which we can calculate payments for compensation that doesn’t affect the viability of the operations? (So traditional owners can build their own human wealth fund to look after their own Native Title groups.)

- What’s the best way companies can offer contract supports for Aboriginal businesses?

- What’s the best way we can have Indigenous environmental management and monitoring of mine sites?

We established a range of principles which are the ‘Kimberley Minimum Standards’ and when I look back on them, there was no rocket science to it - it was just the right thing to do.

I’ve been around the world lecturing with different groups, in Canada and Alaska, in Papua New Guinea, and New Zealand, about minimum standards and how to engage with resource companies. I believe that if you can raise the bar, then you’ll raise the standards, and everyone will rise with that opportunity. Because the racial wealth gap is so huge, no amount of government funding is going to bring equity and proper equality. So, we have to take responsibility for driving those changes and find a balance ourselves.

Who have been some of the key mentors in your life?

Look there’s a lot of people who supported me, mentored me, and influenced me. My father, my grandmother, senior Aboriginal men and women, cultural leaders. They all had an impact. Plus, my family values in terms of what is right and wrong.

As I move more into management and the public eye, there’s different values you meet with people and take on.

Pat Dodson was certainly one of the earlier leaders that I always looked up to because he had such a command of integrity and respect when he talked about things.

Peter Yu, the former KLC CEO, was always very articulate. Both of these people had a huge effect on me.

From a cultural point of view, some of the people who shaped my life with my cultural values were some senior men from Fitzroy Crossing.

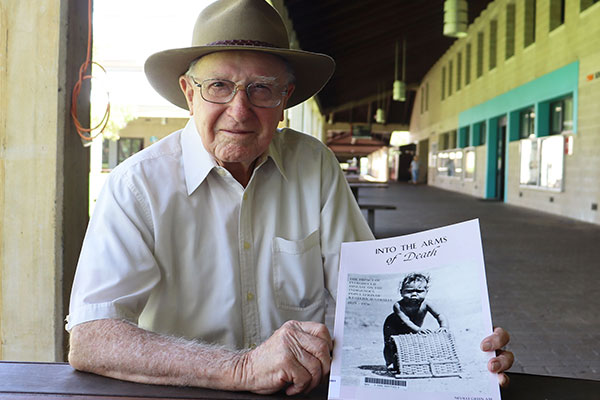

An old bloke called Joe Brown who would be like my grandfather. He often talks about growing me up, that I was a little puppy. And he grew me up into what I am. When I gave my Press Club speech, he came up to me and said ‘Remember I said you were that little puppy and you had to follow me around? Well now I feel like I’m that little puppy and I’m following you around’. It was the most beautiful thing to know that you’ve got that support.

There are other people that have inspired me about right and wrong. One of the earlier speeches that I read from 1964, Malcolm X - The ballot or the bullet.

It became more of a framework for how I saw Aboriginal economic independence. He talked about being aware of how the economy works. I’ll put it in my words here, but essentially, if people come to your area and set up a corner store, and take your money in the corner store then go back to their rich, wealthy suburbs, and take the money you’ve given them in the store, where do you think they spend it on the weekend? They spend it in their community. So what it means is, your community gets poorer and poorer because they take and take, and their community gets richer and richer because they invest the money by spending it in their community.

It was profound thinking I thought and became the fundamental economic principle that I had. We needed to create an economy where we supported ourselves, spent more money in our community, so that our community can get richer and richer, and we have a good society. We have a society where people can grow up and contribute to everything that’s important to us.

Leaving boiler making and working at the Aboriginal Kimberley Law and Cultural Centre (KALAC). Would you say that was life changing?

Yes, I was working out on a cattle station. I was already a boilermaker/welder, and I couldn’t finish a job. The person working with me, Alan Lawford, told me come back to Fitzroy Crossing as there was a trainee apprenticeship for an art co-ordinator in the Aboriginal Art Centre. I went there and was interviewed. A number of things happened. I met my wife that day - which was the best decision I think I’ve ever made!

Then, when I was working in the Art Centre, the senior men asked me to be involved and apply for the job of KALAC which had moved from Broome to Fitzroy Crossing. That’s the job that I remember saying to myself every day, ‘I can’t believe I get paid to do this job.’ It was just the perfect happy spot. That was the job in which old Joe Brown was my chairman. We would go out to numerous remote communities, and I’d sit behind him, and he would conduct meetings in language and then he would turn around and ask me the government position, or what correspondence we had. Then he would turn back to the circle and speak in language. Then there would be a resolution and then they’d turn around and tell me the outcomes, and I’d have to implement them.

It symbolised that image he had of me being the puppy dog that he was training up and I was following him around.

KALAC was so fundamental to my respect, leadership and support, and my foundation as a young Kimberley Aboriginal man. It set me up I think and gave me the foundation to be able to do a law degree because the fear of failing kept me going. I did not want to fail because everyone knew that I was down in Perth studying and they were expecting me to come back.

So yes, it provided a pivotal point for a lot of things that happened to me and kept me, I think, on the straight and narrow.

As you said in an ABC interview, you were a bit of ratbag when working as a jackeroo. Looking back, how do you think you managed to turn things around?

As a young juvenile in Derby, I did a bit of break and enter. I ran amok and got into a lot of mischief. The local JP sentenced me to a community-based order, where I went out and ended up working with my dad on cattle stations.

I think what happened is it just got me out, got me on a different path and kept me away from bad influences. I also understand now the science of the brain. My brain never really matured until I was about 24. My chemical imbalance would have had me making wrong decisions. So, by being out on a station working, being away from potential mischief, kept me on the straight and narrow. A lot of other friends that I went to school with never had that opportunity.

The ultimate result of that is we are in the process of finalising a $14 million Youth on Country project to help take kids who are causing a lot of problems in town, breaking and enter, stealing etc. and bring them out on a cattle station and provide them with an opportunity for a good life. Give them some skills to get a job and hopefully keep them on the right path.

My early childhood days had a bit of mischief, but it also created an opportunity for what I’m doing now and hopefully giving back something. My family was strong, rallied around me and supported me. Maybe I can do that to those who don’t have the same sort of family support structures and they might get a better chance in life.

You have had significant economic impact in the region.

I was really influenced by the things that happened in my life. Working in the three roles I have talked about, it became really clear that if you want to control your destination, you need to control the economy around you.

I believed, with the senior people I was talking with, that unless we had culture in a melting pot in the modern economy, it wouldn’t survive. So, we had to create an economy that we could all live with. That means you had to have mining agreements that had a balance between participants - indigenous participation in the project and opportunity. As well as giving people the space to walk in both worlds, walk in their law and culture, be proud of that, and also walk in a western world. We wanted to create opportunities for our young people where they could be strong, cultural people or they could walk down St. George’s Terrace and get a job.

And so that was where there needed to be an indigenous economy that we controlled and managed, because as the owners and bosses of those businesses operating in that economy, we can find our own balance. We can make it work. I think the Kimberley has been very successful in that.

I’m the Managing Director of a business in Fitzroy Crossing that owns a number of hotels and supermarkets. It’s controlling the economy of that region. It provides lots of opportunities for traditional owners.

In one of the jobs when I left the Land Council, we set up the Kimberley Agriculture and Pastoral Company (KAPCO). It taught me that western capital does not fit neatly into supporting indigenous business. We had to grow it ourselves. Now it’s a $100 million business, running about 38,000 head of cattle and it employs up to 70 people during peak season.

The Aboriginal Ranger Network is probably $65 million worth of wages and project activity a year, that we’ve managed to create. Businesses and opportunities that drive the spending in our local region, which hopefully should create more of a multiplier effect and support not just the Aboriginal community, but the wider community for how we spend and live in that region.

What has it been like running the National Indigenous Times?

There was a lot of people questioning co-owner Clinton Wolf and I, as to whether we were making the right decision to invest and grow the paper, but it’s seen steady growth over the last three years.

We’ve grown our readership to 100,000 online readers a month and about 900,000 papers a month are delivered around Australia through a partnership with Seven West Media and News Corp.

That is going to expand again around Australia with every state and territory. What was so exciting about it, is that it was just a very simple business concept. It wasn’t about making money. It was all about having an indigenous voice to tell positive indigenous stories.

One of my proudest things was having young Aboriginal people come up to me and say, ‘I read the National Indigenous Times because it’s the only place we can get positive stories about Aboriginal people doing good things.’

I’m very proud of it, and proud that we’ve found a little niche. We’ve signed up sharing content deals with other Aboriginal groups in New Zealand and Canada and the US and we are starting to make an international footprint.

So, it’s been a bit of a fairy-tale of how fast it’s growing and how much praise we get. Plus, it’s not just the Aboriginal people reading it. I get approached by lawyers, teachers, auditors etc. and they say ‘Hey, we subscribe to the paper and read it. We love it.’ So, it’s another one of those things I’m proud of and couldn’t believe would happen.

What remains your burning ambition?

I was very fortunate to sit in a number of organisations that had high profiles and a high expectation to be a voice for Aboriginal people. I was blessed with that opportunity to be in those positions and create that influence. So, I try to use whatever context I have to do good.

What I believe I’ve learned in life is that you spend probably the first 40 years in life being confident and trying to learn who you are. And the next 40 years in life should be used putting your learnings to do good and make a difference.

And so I look back now and say… I would like to see the next legacy of Aboriginal affairs be the enjoyment of Native Title. I would like to see the constitutional recognition of Aboriginal people. I’d like to see an organisation that can represent the voice of grass roots Aboriginal people. And I would like to see Australia come in line with the rest of the world and create structures where there can be treaties, negotiations and settlements.

Because one thing that I’ve learnt in my region, is back in the 1880s, the sovereign power of the State created pastoral leases that allowed the State and private families and corporations to build the economic wealth of their society, while our families were locked out in reserves and had to get permission to work.

I would like to see the pendulum and the balance swing back, where Western Australia can do good and settle a lot of those things. We were locked out of the economy. We weren’t able to own land. We weren’t able to build our economic base. But I think I’ve demonstrated in the past six years that we can run businesses and pastoral stations to the level of anyone else.

So, I’d like to see, through this treaty/voice/truth process, that we can reconcile and the pendulum of justice can swing back. One where we can be properly compensated, or have a process where we can have a resolution and our place firmly stamped. We will never make up for the opportunities lost. We just need a more equal playing field.