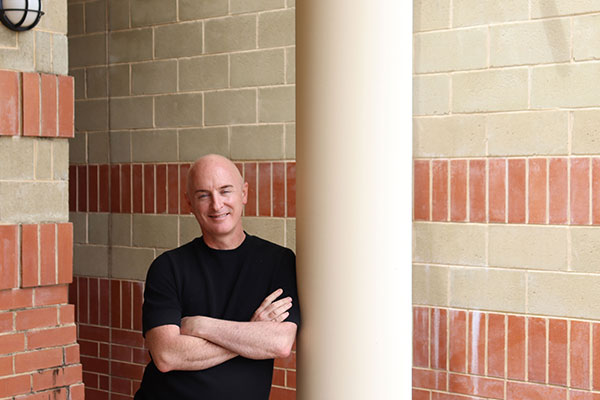

We continue with the second instalment of an in-depth interview with Murdoch University Art Collection Patron, Mr Alan R. Dodge AM

Back in the mid-1970s you were a man from snowy Maine, working at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC before coming to Canberra, the capital of a roasting hot country that was completely culturally different. Was it a shock?

I think my first year was miserable. I realised that even though we spoke the same language, attitudinally it seemed we had very little in common. It was like landing on Mars in a way, and that is when I realised how different the American attitude towards things was compared to an Australian’s view. I had already met Australians who were highly educated and lived all over the world and suddenly...

You found yourself working next to a porn shop in Fyshwick!

Exactly, that is where our first National Gallery offices were. Canberra was a place of two worlds. It was the world of federal politics and the diplomats, the universities, and the CSIRO. And at the other end of the spectrum there was what I called the ‘Tammy Wynette world’ - the utes with the blue heelers in the back. At the time they seemed to be living in parallel universes.

A period of adjustment then?

People kept saying ‘Doesn’t Canberra remind you of Washington, DC?’ What they meant I think was the presence of so many traffic roundabouts in Canberra, like Washington, because there was nothing else that reminded me of that city. I didn’t see any connection at all except that there are national institutions in both cities.

But the National Gallery was so exciting as a project. And the Director, James Mollison, he wasn’t always the easiest man to work with, but boy he was inspiring and if you could convince him that you had a great idea, he would back you.

I began as the Senior Research Officer, which meant I did the research for acquisition proposals to go to the Council of the National Gallery. After time in New York city in the 70s, I came back and helped to set up the Education, Publications and marketing and Public Relations departments, keeping the Publications and marketing for my own role. However, I went to Mollison one day and said that I was disappointed that I had set out to be a curator at the Gallery, but I seem to be used more and more in the administrative areas. The Director said, ‘Well, I will make you a curator.’ I said, ‘If you do that, then the other curators are going to raise hell because I haven’t been doing curatorial work since the end of the 1970s.’ So Mollison challenged me to come up with my own proposal to justify the transition.

I went home and a copy of the Maine Times had come in the mail and in it there was an ad from Dartmouth College, one of the Ivy League universities in New England. It had a new intake for people who had already been out in their career for at least three years called a Master of Arts in Liberal Studies. Applicants had to qualify academically, but the applicant also had to propose what they were going to do as their graduate thesis or project.

The program had coursework required including courses created by two or more professors from different disciplines who would get together and create a course. For example, one of the courses I did was with the head of the Art History Department who was an expert on 19th Century American Landscape Paintings. He got together with a geo-physicist, and we had a course that looked at the development of landscape paintings from the 17th Century to the 20th, alongside of geo-physical theory and geology, and how that knowledge came to be in the 18th and 19th Century and how they influenced each other.

So, this is the mid-1980s?

Yes. I went for one term in 1985 and two terms in 1986. I moved to New Hampshire and then came back in between. I called it my ‘Mid-career Masters’ then because I was 40 when I graduated in 1988. I remember thinking at the time ‘I was living on Dartmouth’s beautiful campus and benefiting greatly from the academic offerings, but felt that this was the loneliest and most selfish thing I have ever done in my life.’ I was living like a monk for three terms halfway around the world from Canberra and my home.

I wrote my thesis while back at the National Gallery in 1987. What I had done essentially was to prove academically that I was on par with the other curators. Mollison and I had done a deal. He agreed to pay me my salary while I was away, plus assist with tuition expenses based on successful performance. I was also granted a substantial scholarship from Dartmouth College, which made the whole exercise possible.

I wasn’t gone two days for the first term when the curators marched down to the Director’s office to complain about the fact that he had given me a scholarship to study when they had all their own wonderful projects.

What did he say?

He said, “Well Alan came to me, and he is producing an annotated a bibliography of writings on Minimal Art as well as producing a thesis (‘Object and Content: Meaning in Minimal Art’). He has also committed to curating an exhibition of our Minimal Art collection which has not been given proper attention so far and yet is a major part of our international collections.”

So, you had come a long way since that first interview when the Director was stand-offish?

I said, ‘Don’t laugh but I want to do a thesis which questions whether there is meaning in Minimal Art.’ He asked me to clarify, and I said, ‘Well isn’t that what everyone asks when confronted with the mute, minimal shapes and so forth...what does it mean?’ I thought there was an investigation that should be done about the fact that Minimal Art was created as a philosophical and political statement by the first generation of artists who had degrees in art history and philosophy, thus it was tricky territory as the artists themselves were the most articulate spokespersons for their particular theories.

I suggested to Mollison that, as it was twenty years later, as part of my research I would go back and talk to the artists that were still around and ask them whether now, with 18-20 years’ perspective, there was something we had overlooked? I wanted to examine whether there was meaning beyond that political moment, rather than admit that these artworks were just an artifact of a moment in time. He said ‘Brilliant, go for it.’ So, I did.

How long was James Mollison in the role?

He was a curator with the Commonwealth Art Advisory Board for several years. From I think 1968 until he was made Acting Director of the NGA in 1971. Then he was officially appointed as Director by Malcolm Fraser in the early 1970s and served in that role though to 1989. At that time the Board decided it would only extend his tenure for one more year. I think there were some political mutterings. So, Mollison left and became Director of the National Gallery of Victoria until his retirement. He died in Melbourne two years ago, aged 88 leaving a legacy that would be a hard act to follow!

So, when you finished at Dartmouth you went back and got a Curator role?

Yes in 1986 I had finished my course work and returned to Canberra permanently, staying at the National Gallery from then on. In total I worked at the National Gallery for 21 years.

How did you become a Curator of Special Exhibitions?

Mollison initially made me Curator of European and American Art. However, there were two other Curators of European and American Art. Michael Lloyd, the Senior Curator, and David Jaffe, who was an expert on Rubens, as well as Michael Desmond who was Assistant Curator. I realised pretty quickly that I could be more effective in another role.

So, after a while, I went back to Mollison realising that there was no-one overseeing the major international and Australian exhibitions that we were mounting at least every 18 months. There was the curatorial knowledge, but curators didn’t always oversee all the elements such as negotiations for loans, the publications, hang the show, install it, the design, etc., and these projects needed someone to oversee everything from the marketing through to the curatorial aspects. So, the Director made me Curator of Special Exhibitions.

You invented a role again?

Yes, and that was the last job I had there. The next NGA Director, Betty Churcher, built the role, but also kept me in the role as Advisor to Development as well because I had set up the Foundation some years earlier as one of a number of responsibilities I took on.

Was that the first kind of role like that in Australia?

They had Exhibition Officers in other Australian institutions, but they weren’t quite the same thing.

Plus, if it was a show that Mollison or subsequently Betty Churcher, sourced from a single lending institution, they would send me to finish negotiations and coordinate details of the exhibition. As a result, I had the opportunity to meet Directors and Curators from all around the world, which, when I came here to Perth, meant I had a strong network which enabled us to do all the big exhibitions we did at AGWA including ‘Monet & Japan’ which was an absolute coup. We broke all records for attendance with that. We followed Monet with a major exhibition of Auguste Rodin.

My favourite project at the Art Gallery of Western Australia was an exhibition I sourced from major Russian institutions called ‘St Petersburg 1900’, which took ten years to negotiate. We got just about every artwork I asked for because I had proven to them that I was passionate about Russian art and culture, plus I kept going back to Russia and built-up trust. Finally, during my tenure of eleven years, we ended with a big show of Egyptian antiquities from The Louvre, which we shared with the National Gallery and the Art Gallery of South Australia.

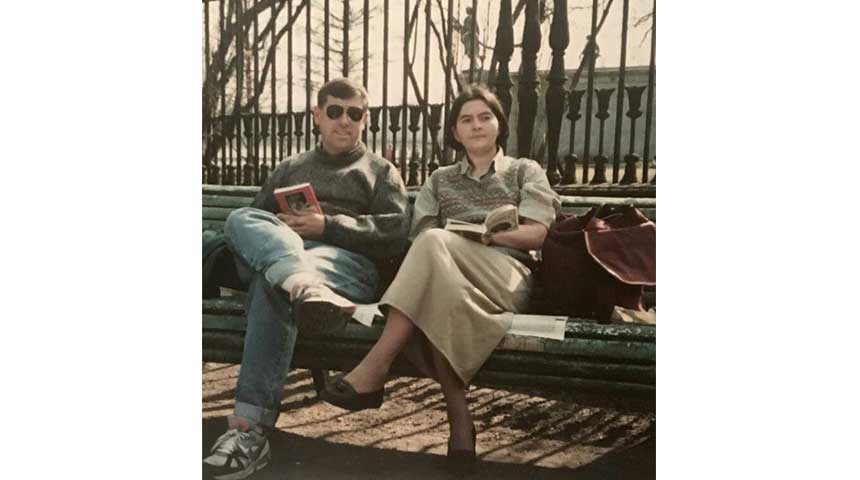

Moscow 1995, with Russian friend and colleague, Elena Kasyanenko, outside the Sheremetevo Palace in St. Petersburg. Reading the poetry of Anna Akmatova in the courtyard outside the window where the poet lived.

With all the special exhibitions, what was the most satisfying one to work on?

‘Saint Petersburg 1900’ - the Russian show. In the early 1980s I knew very little about Russian avant-garde. All that work in the Soviet Union had been hidden in storage. I found out later that most museums often purposely mis-catalogued it, so that it would never get found and possibly destroyed. Other than a slight thaw during the Khrushchev era, the work never saw the light of day. Anyway, when doing research for my thesis at Dartmouth, I found out that a few of the Minimal artists in New York had made references to the Russian and Soviet Avant-garde and wondered how they secured the knowledge of these activities. An English woman named Camilla Gray, who lived in New York and worked at MoMA (Museum of Modern Art) turned out to be the source. She became an expert on Russian art, married a Russian and moved to the Soviet Union and had access to all the archives because she was a Communist herself.

Camilla Gray wrote the first major book in English on the subject titled ‘The Great Experiment: Russian Art 1863-1922’ about this whole avant-garde era that led up to, and followed, World War I. It was published in 1962 in London and New York. To this day, it's the book on the Russian avant-garde for the World of Art series by Thames and Hudson.

I read Camilla’s book and thought it was marvellous. I convinced Betty Churcher in 1990 that she, Bill Wright from the Art Gallery of NSW, and I, should go to Moscow and see if we could do an avant-garde show. She sent me three days ahead because she feared going on her own to Russia. So, I went ahead alone, and I was put up in a hotel set up for visiting lesser oblast officials which was opening its doors for the first time to foreigners.

As a result, a Japanese businessman and I were the first foreigners they allowed to stay at this hotel. The access occurred because they needed foreign currency. On the first morning at the hotel, I put on my shorts and went out running. I ran around Gorky Park, and when returning, I came around a corner a woman spat at me. I got back to the hotel and while speaking with an attendant, I told him about the woman who had spat at me. He laughed and he said, ‘You know why, don't you’? I said ‘No’. He said, ‘because you are wearing shorts and men don't wear shorts in Russia for sport.’ He added that ‘you could wear no top, but as long as you have long pants nobody will look twice at you.’ And he was right as I found out the on the next day’s run.

I had Saturday morning free and wanted to get into the Kremlin, but I wasn’t sure how. I went down to the Kremlin walls and saw a line of people queuing by one of the gates, so I just got in the line. I found myself amidst a private girls’ school from Connecticut. One of the teachers told me you had to have an in-tourist ticket to get in. I was about to leave when the group leader said, ‘Well one of our teachers is sick, I've got their ticket, you can come in place of that teacher.’ So, I got in. There I met one of the Russian guides and ended up taking her out to dinner. Over our meal together, she told me the whole lay of the land basically, which was a big help.

For Betty Churcher and Bill Wright and me, I think the trip was a bit of a revelation. We made good contacts with the help of the Australian Embassy. However, nothing came of that trip right away. I realised that success would only come from persistence, so I began a series of regular visits over the years. Plus, I won a travelling scholarship and lived in Moscow for three months in 1995 which was invaluable as negotiations needed more time than a quick visit. Often, I would go to scheduled meetings and people wouldn’t show up, or they cancelled the meetings. It wasn’t because they weren’t being considerate, it was just that life was so complicated then. Just getting through everyday things, like going to the doctors, or finding food or toilet paper, was really difficult.

Overall, a great mentor for organising exhibitions, Bob Edwards, the Head of Art Exhibitions in Australia (which is the corporate body that helps fund and organise exhibitions), told me what to do. He said ‘Every year spend three to six weeks, go round the world and go to as many cities as you can. Take every Director/Curator out to dinner, even if you have no agenda, find opportunities and just keep wining and dining them and keep going.’ Sure enough, that is what ultimately worked and in 2005 we had this amazing show from Russia, exclusively in Perth, as well as many others.

Did you get good reviews?

Yes, and amazing publicity. Anyway, this is why it was my favourite show. Leading up to the exhibition I woke up one night in a sweat, it would have been a year out, I guess. I thought ‘OMG nobody is going to know the name of a single Russian artist’. Only the cognoscenti would know names like Kazimir Malevich, Liubov Popova, Alexander Rodchenko, Varvara Stepanova and the like. And I needed people to pay for it! So, I thought ‘What do I do?’ Then I thought ‘Well people know who Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky were, and they know who Tchaikovsky and Stravinsky were… which gave me an idea.

The next morning, I called the head of every institution in Perth that I could think of and brought them in to the AGWA Board Room. I said ‘For years I have been watching people doing exhibitions about the Russian avant-garde and showing how it came out of Futurism and Cubism. What I want to do now is to show the Russian roots of it; to include the icons and the popular prints, folk art, shop signs and all the elements that influenced why Russian avant-garde looks Russian.’

I explained my dilemma. Concluding with, ‘What if we do a festival of Russian culture?’ The City of Perth offered to umbrella it all and market it as a Russian Winter Festival in Perth. It became the first winter festival.

With Elena Kasyanenko again and art historian Elena Bespalova at Christmas Eve dinner at the House of Writers, Moscow, January 2020.

You were pretty fearless going to Moscow for three months.

I wasn’t fearless at all, I was dumb! I didn’t think about the consequences too much.

It certainly was a challenge. 1995 was the period under Yeltsin as Russian President. At this time there seemed to be a major breakdown of law and order. Mafia gangs were fighting for territory. There were drive-by shootings on the street. Amazing things happened to me. I felt some threats there, but I had also never felt so alive in my life! It was among the greatest moments of my life living and surviving on my own in Moscow.

How did you come to finish up at NGA and make the move over to Perth?

In 1996, Sir James Cruthers and then John Stringer called me to tell me that the Directorship of the AGWA was coming up and they both basically said, “They need you here”. So, I applied against a very good field of applicants. I knew nothing of Perth, so John Stringer suggested that I come over before the interview and spend a few days checking out the city. This I did and for two days acted as a flaneur, which I quite liked. I also, of course, visited the AGWA. Once inside, I could see its potential.

I had an interview at the headquarters of a head-hunting company in West Perth. It was a very interesting experience as the committee featured Prof. Margaret Seares AO, ceramicist Joan Campbell (who sadly is no longer with us), the then Chairman of the AGWA, Lloyd Guthrie, and the head of the Department of Sport. It was a lively and positive interview, but I went back to Canberra with no expectations. However, I was summoned back to Perth a few months later to meet the then Minister for the Arts, the Hon. Peter Foss QC. By November 1996 I was appointed Director of the AGWA with the understanding that I would take up the position in early January 1997 which I did.

At the NGA, I finished my last big project as Senior Advisor, Special Exhibitions with the wonderful curator Jane Kinsman, which was ‘Paris in the late 19th Century’ a beautiful exhibition in partnership with the Musee d’Orsay in Paris.

It was hard to leave the NGA, but the lure of having my own project to shape was too tempting and it proved to be a wonderful, if at times, trying experience. Part of the reason for my enthusiasm was the encouragement of NGA Director Betty Churcher, who so much enjoyed her time at the AGWA before coming to Canberra, and who assured me that I would love living in Perth.

The AGWA that I inherited had very good staff who rose to a vision that I wanted to give to the institution and from there we started an 11-year adventure together.

Alan receiving Murdoch University Honorary Doctorate from Deputy Chancellor Eva Skira in 2012

You grew up in Maine, came to Australia in the seventies, jet-setted around through the nature of the job, do you feel Australian, or do you feel like a global citizen?

No. I feel Australian. I am at the point now where when I go back to America, it takes me a while to find my way back into my American self. I think that is a lost part of me in a way. I have family in New England and New York, but I have been here now since 1974 with just those hiatuses in New York and Russia. Yes, I have been all around the world, but I think if I were to do a psychology test about attitude, I would probably come out as Australian.

I also think there is something about adopting a country as your own. It is not something you inherited; you must make your own space. To me that is more valuable. Maybe that is why I feel more attached to Australia than to America.

How did you become involved with Murdoch University?

I was invited to join the Art Board. I wouldn’t have taken on the Board role if we hadn’t had Mark Stewart, the Curator. He does the work, and the research. It was great to be on the outside, coming in and chairing the Board because I wasn’t weighed down by any bureaucracy.

When they asked me to be Chairman, which was under a previous Vice Chancellor, I agreed under the proviso that we needed to establish a memorandum of understanding, an agreement and establish a budget for acquisitions.

If we had that freedom and commitment from a Vice Chancellor, I thought we would be able to do it. I believe an Art Board won’t function at a university without direct access to a VC and a curator. A curator such as Mark is there to enrich the collection, to enable it to be one of those ‘free your think’ experiences for Murdoch university. That is what we are building.

What would you say universities do well when it comes to having an art collection and what do they do not so well?

I think the original idea behind art collections at universities was that artworks would look nice in the boardrooms and offices. I think the transition that has taken place is the realisation that a collection can be so much more, including being a teaching resource.

It can be an enhancement of visual thinking and an entrée into problem solving. It might be just original wallpaper to some people, but for other people it triggers ideas. It enhances the richness of their existence.

Campus life is something that hasn’t really been developed in Australia, compared to say somewhere like the US. I think it is up to universities to really enhance their campuses, so people use them as more than just as a learning institution. Developing them as a community magnet, somewhere to come to concerts, exhibitions, and lectures. So, the university acts as a porous university, that whole idea of getting people moving through the campus to enjoy it in different ways and learn from it and use it.

At Murdoch we have built a great collection from very little, which is displayed throughout the campus. I think the future will be enhancing that porous university aspect and having even more exhibition spaces so that when people are filtering through, they can enjoy these things as well as be stimulated by them intellectually.

I am thrilled to still be involved. We have got the groundwork here for something that the other university campuses don’t have. I love the campus, there is just something special about it. Originally, when I was asked to come out and see the collection, I suspected they were going to ask me to be on the Board and I was going to say no. And I walked away saying yes! Lo and behold within a year I was Chairman. I think of all the projects I have had in Perth, other than the Art Gallery of WA itself, it’s been my favourite.

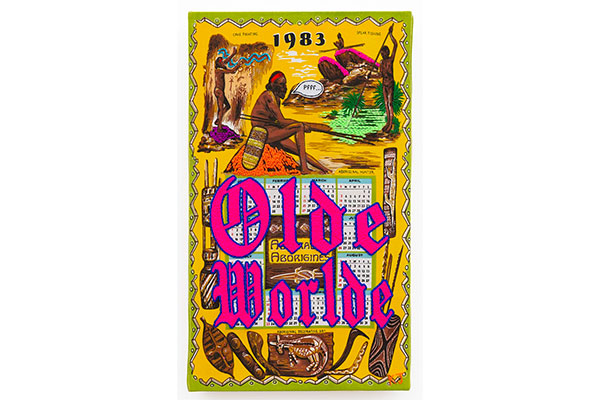

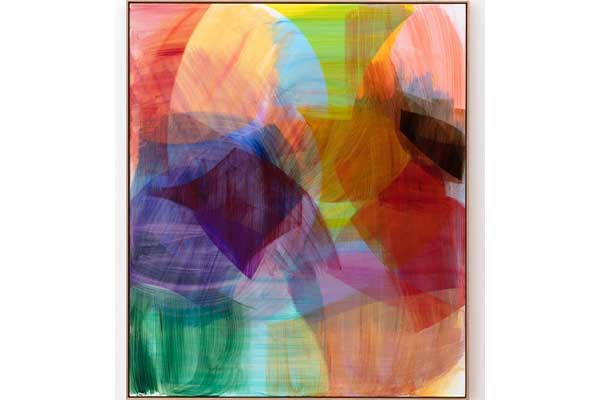

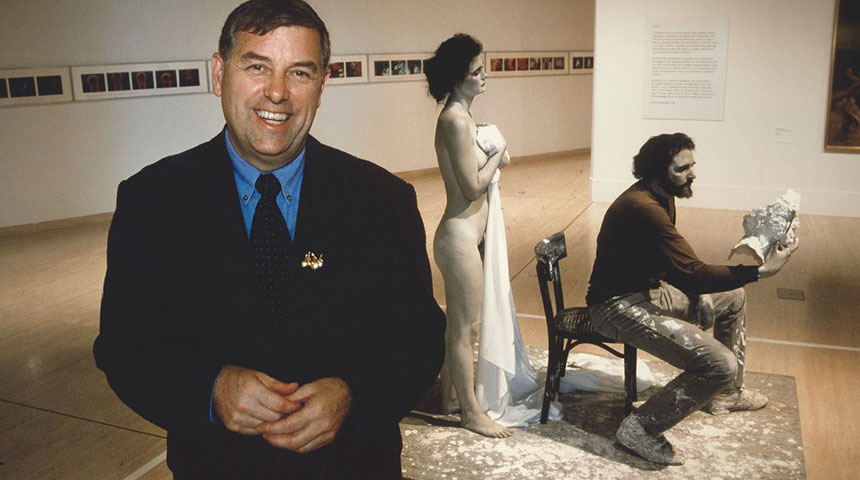

Alan in 2002 while AGWA Director, with works from the Gallery's permanent collection (Photo by Steve McCurry)

(Special thanks to Nik Babic for use of his portrait photo at top)