Blog

Maine man of letters

First of a two part interview with Murdoch University Art Collection Patron, Mr Alan Dodge AM

As part of the preparations for Murdoch’s 50th anniversary in 2024, the University has appointed a patron to develop a landmark celebration of the MU Art Collection. An ambassadorial role, the patron will work with donors, curatorial staff, and the MU Art Board to create a campaign to showcase the depth, diversity, and historically significant elements of the globally respected collection. Already a familiar name to the Murdoch community, Mr Alan Dodge AM was a natural choice for this prestigious position.

Alan’s 40+ year career in the art world has made him a global name. In 1972 Alan became a lecturer in the Education Department of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. In 1975 he was appointed the first Senior Research Officer of the fledgling Australian National Gallery (now National Gallery of Australia), where he stayed for 21 years. During that time, he held a number of positions, culminating in the role of Senior Advisor, Special Exhibitions and Development. In late 1996 Mr Dodge was appointed Director of the Art Gallery of Western Australia, a position he held for eleven years until the end of 2007, when he retired.

Mr Dodge was made a Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, by the French Government in 2004, an Honorary Fellow by Edith Cowan University in 2007, and was recognised with an honour in the Order of Australia (AM) in 2008 for service to the arts.

He was named Western Australia Citizen of the Year, Culture, Arts and Entertainment in 2011, and made an Honorary Doctor of Letters by Murdoch University in 2012 and a Doctor of Letters by Curtin University in 2018.

Currently on the Vice-Chancellor’s Strategic Advisory Board at Murdoch University, Alan was the longest serving Chair of the MU Art Board, managing the collection from 2009 to 2017. Over the last couple of decades he has also been one of the most generous donors to the Murdoch University Collection.

Backlight will attempt to distil some of the milestones of his rich and broad career into a two-part interview. In this first part, we cover the aesthetic awakenings of early childhood, through to Alan’s work at the freshly built National Gallery of Australia.

Where did you grow up?

I grew up in a place called South Portland in Maine in the United States, about two hours drive north of Boston. I would equate it to growing up in Tasmania. Even though it wasn’t an island, in many ways it was an island! I graduated in 1965 from high school and went onto university, graduating in 1969. To picture my high school, think of something out of ‘Happy Days’ - the drive-in burger place with the roller-skating waitresses, etc.

Alan's childhood home in South Portland, Maine, USA

When did the world of art first grab you?

I would say from the time I was around eight. I was taken to the Portland Museum of Art which included a grand Georgian mansion built the same year as the White House. At the time it displayed mainly American and New England work, although it had some European art. I walked through its beautiful hallways and saw all these lovely paintings. A lot of them were by Andrew Wyeth and his father, N. C. Wyeth. Andrew created ‘Christina's World’ which everybody knows.

I just remember thinking ‘this is a world I don't know’ because, although my parents were well educated, I don't think that visual art was a big interest in their lives. I thought here’s this new world of elegance and beauty and I would like to be a part of it.

I also had a friend, whose parents were very musically astute with a great recording collection. We'd listen to Rimsky-Korsakov and Rachmaninov in their living room on their record player. Once again, I thought “What must it be like to go to a theatre and see an orchestra, or an opera?!” I began to think that I wanted to be part of that world and art seemed like the most exciting part of it to me.

I've never looked back from that. I did not know how I wanted to be in that world, but I just knew. Initially it looked like I was heading to be an artist myself. I wanted to be an art major at university, however, my father told me to become an electrical engineer, because that was the way of the future.

What did you think about that?

I said to my Dad ‘I want to go to university, but I want to study art.’ My father’s response was ‘You'll never make a living from art’ which of became a standing joke in my family because I am the only one who has made a career out of what they said they were going to do.

Was that the only drive you needed to make it? The old ‘I’ll show you’ thing?

I don't think it was purposely like that, but I was determined to do it. I told my father that I would earn my own way through university, having no idea how to do it, although I had a job every summer and saved my money. I also secured part-time jobs on campus and I received a few scholarships at university.

Mind you in those days it didn’t cost all that much to go to a State University. I went to the University of Maine and had a wonderful time. They had a major in Fine Arts which was the combination of art history and studio work. I did the equivalent of an art school diploma as well as an art history degree.

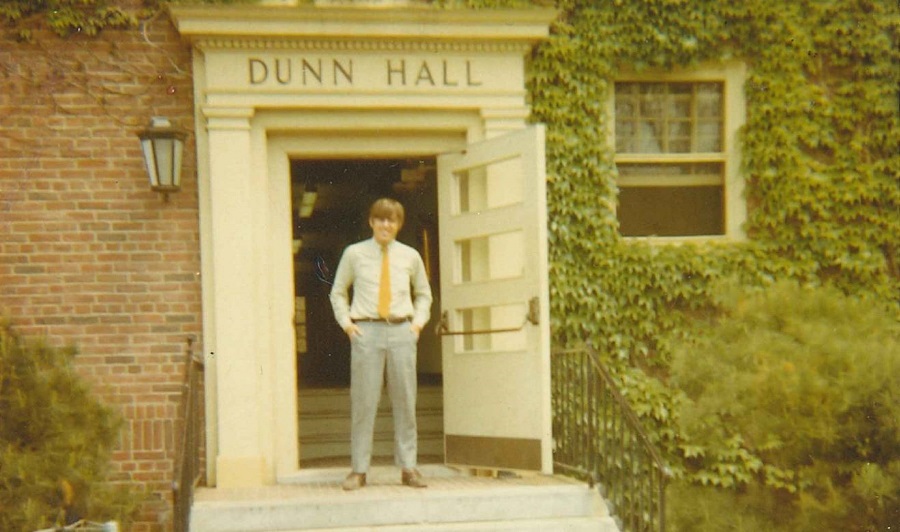

Graduation Day 1969, University of Maine, Orono

The only thing that my university thought you could do if you weren't an artist yourself, was to teach and I just didn't think that was what I wanted to do. I'm so glad I stuck to my guns. At university I started taking more art history courses. It turned out I was much more interested in why someone like Lorenzo de’ Medici, would hire a Neoplatonic philosopher (Marsilio Ficino) to write programmes to have paintings created by Botticelli for the edification of his nephew than actually making things. I thought ‘why would you do that?’ Those kinds of questions were far more interesting to me than anything I thought I had to say visually on canvas or paper.

What was the next step?

I knew then that I wanted to be involved somehow with the art museum world. However, like everybody else, I had to do some time in the military because of Vietnam. You could go to university, but not beyond, unless you were in medicine.

When I got out of the Navy, I went back to Maine and I convinced the new, young Gallery Director, John Holverson, at the Portland Museum of Art to hire me to work painting walls, hanging shows etc. for $2 an hour. Meanwhile, I found out that part of John’s job was to teach the art theory courses at the Art School next door. John had sprung a surprise essay quiz on his students and was so disgusted with the results he refused to grade them. I offered to grade the essays and put comments on them. He said, ‘Well you can take the class!’ So I did and teaching was added to my duties at the museum.

Naval service 1970

Your first job in the arts!

Yes it was, though I was struggling to get by financially. I had a job at night waiting tables in a lobster restaurant. One winter night after waiting on tables in a half empty restaurant, which meant I barely raised the petrol money for the commute in tips, I really felt things would have to change. When I got home I had a pensive walk along the beach in the snow. It was freezing cold, about -8 degrees. The whole future felt rather bleak. When I got back to the apartment I just thought ‘Where am I going with this?’ I knew that staying in Maine was a dead end and that I had to do something.

I sat down and made a little chart. It had goals, three years from now, four years from now etc. where I asked myself what exactly it would look like if I were actually doing what I wanted to do within five years. I concluded to get to my goal I should be working at the National Gallery in Washington.

I thought ‘All right, that’s a goal, now how the hell am I going to get there?’ So I wrote them a letter.

Did that work?

Not exactly. It’s a long story. Eventually, I secured work as a temporary education curator there and before long a permanent Education Curator had to leave. I was among the last two candidates for the job and a woman who was up against it with me was the other temporary Curator there. She backed out so that I could get the job, and then she got the next one. Her name was Fran Feldman, a wonderful woman. So, I got my job at the National Gallery.

Do you think you ended up working in museums and in the kind of positions that you had, because of the whole aesthetic?

Well, it was on another plane to the life I was living with my family. I know it was probably seen as a world of privilege too, but I didn’t see it that way. I saw it as a world of excitement, and glamour that I didn't have. More importantly, I understood that it was a world of ideas as well.

How long were you at the Gallery?

I was there for just over two years. One day, it was Guy Fawkes Day, 1972, an Australian came into the gallery and asked to see the Widener Collection of Renaissance bronzes. I fell in love and that’s why I’m here.

Wow!

We had discussions and at the time the National Gallery was being developed in Canberra and we considered that perhaps I could work there. This was during the Whitlam era, when they were beginning to consider expanding immigration groups beyond just English and Mediterranean citizens. During that window I applied and secured my immigration visa. I paid for myself because I wanted to be able to leave if I didn't like it. The administrative staff at the Washington Embassy asked me all sorts of questions like ‘Do you realise the landscape isn’t green, it's grey and brown’? On reflection, I think they were good questions to ask, because in a way it is a bit like entering two million years BC when you see the landscape in Australia for the first time.

You went straight to Canberra?

After an initial few days in Sydney, we boarded a plane for Canberra. This was 1974. We flew an old DC9 into Canberra airport and our friend, Bill, was waiting for us. He drove us around Lake Burley Griffin and showed me the new National Library and other landmarks. As we circuited the lake shore, we passed this great big hole in the ground. I said, ‘What’s that?’ It was only then that I was told: “That’s the new National Gallery.” OMG. Nobody had told me that it hadn’t even been built yet!

Oh no! So, you thought you were walking into completed infrastructure?

Yes. Anyway, I eventually secured an interview with the Gallery, out in a warehouse in the industrial suburb of Fyshwick. It was where all the artworks were, waiting for the completion of the building.

I first had an interview with the administrator and one of the museum assistants. They then said I will have to come back as the Director, James Mollison, was currently overseas. James eventually came back, and I duly dressed in my best suit for the interview. He arrived an hour and 45 minutes late from a long lunch. He took me into his office, sat me down and proceeded to attack me with questions like ‘Why should I hire you, when there are hundreds of qualified Australians who would give their right arm to work here?’

Well, I didn't know the industry as a profession was in many ways in its infancy, so I rather meekly said ‘Well how many have worked in a National Gallery because I have?’ It didn’t go well. He was very aggressive. I thought…mmm, I can’t work with this man.

However, James then said to me, in almost a dismissive voice, ‘I am about to show my lunch guest around the storage bays, if you’d like to tag along’. Those were his actual words which I thought was rather insulting. However, I thought ‘bite your tongue’ because I wanted to find out what they had.

In the storage bays there was a large group of monumental prints by Robert Rauschenberg that had just come into the collection and were being inspected by James’s able assistant Margaret McKeon. On the back wall hung ‘Woman V’ by Willem De Kooning and in its own roll-out case was ‘Blue Poles’ by Pollock. Plus, a big Milton Resnick painting, propped up on a bookshelf, and that was only the beginning. We pulled out some truly impressive art works in our tour of the storage bays. But when I left, I was frankly fighting back the tears thinking that I’m never going to get to work there. The Director just didn’t seem that interested.

Over the next few months I applied for anything and everything and got a job as a maintenance clerk at the new Woden Valley Hospital (now Canberra Hospital). It was really interesting, almost like living in the television soap opera, ‘General Hospital’. Nine months later, I received a phone call from the Home Affairs Department telling me that they would like to interview me for the position of Senior Research Officer for the Australian National Gallery.

At last…

Yes, but I was just one of nine people they interviewed. However, the day after the interview I received a phone call from Mollison himself saying ‘Can you start on Monday?’ I found out later that during the interview, the representative from the public service was handing him notes saying ‘You can’t hire him. He's not an Australian citizen’. And he was handing notes back saying, ‘Well watch me!’ So he hired me under contract to start. I couldn’t believe it.

Day one, I headed to a building the gallery had just leased for office space and to house the museum library temporarily. A round building, which was supposed to be the restaurant for a motel that was never built, it was surrounded by a Venus adult shop, Communist bookstore, and a fly-fishing shop. For eight years the ‘Rotunda’ was the central office of the National Gallery.

There were only five employees. James Mollison sat at a desk right in the middle of the room, with a strip heater under his desk and a blanket over his shoulders to keep warm. It was winter, but there was no heating or air-conditioning in the building, so things were pretty primitive. There were also two secretaries, who needed to wear gloves with the finger ends cut out so they were able to type.

How far had the main gallery progressed in its construction then?

I think the foundations had been started. This was July 1975.

So late Whitlam era?

We had actually been on the Parliament House lawn to witness Gough Whitlam’s famous ‘dismissal’ speech, which was pretty amazing because I knew I was witnessing history.

Anyway, on my first day at work back at the repository at the Gallery a huge crate had just come in. It was a sculpture by Modigliani, based on African influences. With an assistant, I had to un-crate the monumental work and do the photographs and the condition report, having never done one in my life. When we finished and lunchtime came, Mollison came up to the repository, checked out our progress then said, ‘Well, you’ve passed your first test, now you can come down to the rotunda building to start your real job.’ I was the seventh person they hired for the Gallery.

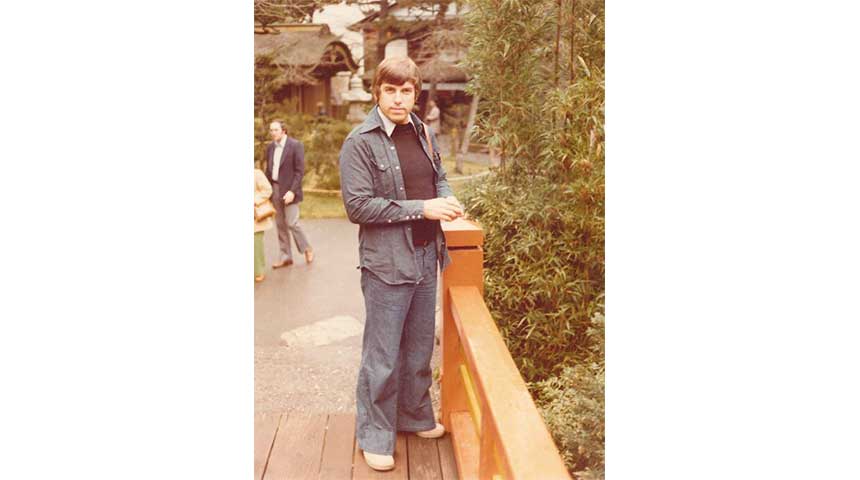

Tokyo 1980, Global trip to establish printing contracts for NGA publications

What was it like to be there at the very start?

Wonderful, we had to develop everything from scratch and had to invent every system we had. We could look at other museums yes, but we had to develop everything for our own needs. Over the time I was at the National Gallery I was instrumental in setting up five departments, including publications and marketing, education and development.

My first title, Senior Research Officer, meant I did the research for purchases. This included preparing reference papers for the Board, called the Council, to help them decide whether to acquire the works we wanted.

However, during this time, my partner, who knew I was unhappy during the time at the hospital, had been applying for postings. He received notification of posting to New York. We found that out only after I had secured the job at the Gallery. It was to be a three-year posting. So, we thought, ‘What do we do now?’

So we invited James Mollison over for dinner and after a nice meal and a fair bit of wine, I said to him James ‘I want to go to New York.’ To my complete surprise he said, ‘Well I want you to go.’ He said ‘I don’t want you to work in the art world over there. I want you to sell shoes or something. But have a free schedule and go look at art galleries and artists’ studios and report back to me. I’ll come to New York twice a year and you can set up the meetings for me. I can’t pay you, but I promise you a job when you come back to Australia.

I was in total shock and said, ‘Why are you saying all this?’ He said, ‘Because I found out today that the Gallery construction has been put on hold while they finish the High Court.’

What had happened was when Malcolm Fraser got into office after the Whitlam debacle, the Chief Justice, Sir Garfield Barwick was building the High Court next door to the Gallery. He had made sure that the Queen was scheduled in to open it, so they had no leeway to delay construction and he convinced Fraser to put all the energy into building the High Court first before finishing the new Gallery next door. For three years nothing much happened, except maintaining the site for the Gallery while the High Court construction went full steam ahead. It was perfect timing for me.

The universe was looking after you.

Yes. We went to New York and my first job was as a private secretary to a Broadway Theatre producer named Clinton Wilder. Clinton was also President of the Mark Rothko Foundation which at the time was subject of a lawsuit, which made it an interesting time to be around. As well, Clinton’s partner, Barney Brown, had the lease of Rothko’s old studio where he carried on his art conservation and restoration work. Two days a week I was farmed out to Barney to do his correspondence and billing. He was very social and people like Andy Warhol and Halston’s (American fashion designer Roy Halston Frowick) models used to come by and gossip, so I found out everything that was going on!

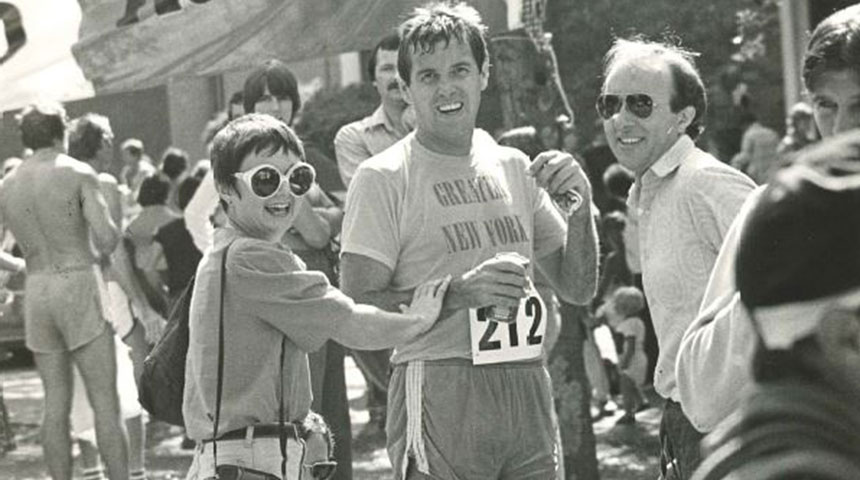

From the time we arrived in New York, I got interested in running and I joined the West Side Y Club and I ran my first New York marathon in 1976.

Alan finishing one of 8 marathons he completed - Canberra 1980

My jobs in New York gave me freedom to constantly scan the gallery scene. The late John Stringer, who was Kerry Stokes’ curator here, was in New York at the time too, working as curator at the Hispanic Society. The two of us would often go around together with one of the curators from MOMA and visit all the dealer galleries and art studios. As this was the 1970s we had no email or photocopy machines so I had to write letters to James Mollison and draw little pictures of what I had seen and make suggestions. Then when he came to New York, I used to introduce James to new dealers and helped set up appointments with those he didn’t already have a relationship with. I didn’t know until I went back three years later that he bought almost everything I had drawn pictures of in my letters! He never told me. I remember when we started installing works in the new Gallery building, he walked me to a Robert Smithson piece. The staff were about to set up this stunning mirror and rock salt piece. James said ‘Well, you are the one who alerted me to this when we bought it, so you can install it.’ Amazing – what a wonderful task!.

At that time, was there much budget?

I don’t know how the politics worked but remember when they bought ‘Blue Poles’, Gough Whitlam made himself Minister for the Arts so nobody could oppose it and then put it on his Christmas card because he knew it was going to be controversial.

What people didn’t realise was what a wise investment it was. ‘Blue Poles’ made the front page of the New York Times, and the gist of the front-page article was ‘Amazing, fabulous thing.’ It was a record price for a modern American work and was going to Australia. It was a complimentary piece. As a result, the Australian National Gallery was the first art museum in the world ever to make the front page of the New York Times because it was a spectacular picture sold for a record price. However, when I arrived in Australia the headlines here included ‘Drunks Did It’. I thought ‘Oh these were arguments that were made back in the fifties. We are now in the mid-1970s. What’s going on here?’ It cost two million US dollars. But that was only about $1.2 million or $1.3 million AUD at the time.

Also, what people didn’t realise was that it was a fabulous investment, because what happened was that every dealer in the world smelling gold in Australia started telling Mollison first what was available at the very highest level. Often art dealing at this level is fairly secretive. A dealer might have someone they would let know what is available and see if they can afford it and so forth. Plus, that dealer might have two or three other people in line, who would have only half the information, to approach just in case the initial deal falls over, because this was major money. So suddenly here is James Mollison sitting in his office in Fyshwick with truly major works being offered to him from Paris and New York and London. As a result the National Gallery acquired many fabulous pieces like Kazimir Malevich's 'House Under Construction', Hans Hoffman’s ‘Pre dawn’ and DeKooning’s ‘Woman V’. That all happened because of the initial investment made in ‘Blue Poles’.

So, a brilliant decision.

It was a brilliant, brilliant move. Strategically it is the best thing that they could have done. I don’t think the public thought that, and certainly the Government did nothing to encourage any positive thoughts about it. But they kept funding the acquisitions to a very high level because they were building the last National Gallery in the world to be built at the time. James came to New York with a chequebook that very few people had. This was before the big spending power of the Japanese, Chinese and Russians. So it was a very exciting time to be there, and we did acquire a lot of great work. Plus, it gave me an entrée to meet all these artists and dealers and get to know the art world - wonderful connections that paid off further down the line.

When did you return?

I came back in January 1979.

Into the National Gallery?

Yes. We were still out at Fyshwick until we moved into the new gallery building gradually from 1981. In the new building we had a year of hearing drills and hammers going while they were still finishing off the building. Only half of us moved in initially. The other half were still out at Fyshwick. Eventually everyone was in and HRH The Queen officially opened the building in October 1982. In the meantime, there was an Act of Parliament that made the Gallery a statutory authority. From that point on I had a permanent job and later I was able to become an Australian citizen.

I understand your citizenship ceremony was held at the National Gallery?

At the final citizenship interview they asked when I would like to have my ceremony. I think they were expecting me to say Australia Day. I replied that I’d like it on Melbourne Cup Day which raised some eyebrows, but I explained how I thought it was the most Australian day of the year. The interviewer explained that nobody else would request that day, but the head of the ACT Government stepped in and offered to swear me in.

I was asked, “Where would you like it?” I said, ‘In the sculpture garden of the National Gallery in front of the Rodins.’ So they set up an easel with a picture of the Queen and NGA Director, Betty Churcher, was on hand to oversee it all.

Citizenship ceremony in 1994 with Trish Maldon and Bill Shippley

To be continued…

Blog

Maine man of letters

Posted on

Saturday 9 October 2021