Digging mammals important for ecosystem health

Areas of research

Conservation

Lead researchers

Trish Fleming

Wildlife Conservation, Harry Butler Institute

View staff profile

Amanda Kristancic

Adjunct - Harry Butler Institute, Murdoch University

View staff profile

Shannon Dundas

Adjunct - Harry Butler Institute, Murdoch University

View staff profile

Gillian Bryant

Adjunct - Harry Butler Institute, Murdoch University

View staff profile

Catherine Baudains

Adjunct - Harry Butler Institute, Murdoch University

View staff profile

Giles Hardy

Emeritus Professor - Harry Butler Institute, Murdoch University

View staff profile---trish-fleming.tmb-960-banner.jpg?Culture=en&sfvrsn=38a19bb5_1)

Australian digging mammals have played an important role in transforming the country's ancient, infertile soils.

Australia’s ancient landscapes have infertile, weathered, nutrient-poor soils that are especially deficient in phosphorous and nitrogen. Australian digging mammals have therefore played an important role over time, turning over soil, increasing water infiltration and nutrient cycling, as well as providing a refuge for seeds and suitable conditions for seedlings to grow [1, 2].

Most Australian native plants (including all our Eucalyptus species) have evolved symbiotic relationships with mycorrhizal fungi to increase their uptake of nutrients and water. Mycorrhizal fungi are therefore important for maintaining plant health, increasing plant vigour and resilience to root pathogens. These beneficial fungi increase the capacity of plants to deal with abiotic and biotic changes.

Many mycorrhizal fungi produce subterranean fruiting bodies—or ‘truffles’—which are highly sought after by many marsupial species that specialise in locating and digging them out. In turn, the mammals disperse spores of the fungi across the landscape [3, 4].

Despite once being described as common, digging mammal species have been lost from the Australian landscape over the last 200 years. Around half of digging mammal species are now extinct or under conservation threat, and the majority of extant species have undergone marked range contractions [5] and are therefore ‘functionally extinct’ in that they are no longer sufficiently abundant or widespread to maintain their important digging roles.

Australian ecosystems have therefore undergone a massive loss of ecosystem processes relatively recently. Effects of these losses—such as reduced plant recruitment and growth, flowering, seed set—are likely still to be felt.

Quenda (Isoodon fusciventer) are one of the only digging mammal species that have remained reasonably abundant across southwest Western Australia [6]. Recognising where populations exist and continuing to quantify and understand their vital role in ecosystem health will help us work towards conservation of our precious urban bushland.

Although they have an omnivorous diet, showing a high reliance on invertebrate prey, bandicoots such as the quenda eat a considerable banquet of fungi. We used DNA barcoding to determine what food items were present in 60 scats collected across a range of urban reserves. Our analysis revealed over 800 different fungi across our samples, each with its own unique barcode. Each scat sample contained an average of 46 different fungi (range 8–120) [7].

We had thought that we would be able to identify which fungi species quenda prefer, but it turns out that our study shows us just how few of our fungi have been genetically identified previously. We could only assign 20% of the fungi to known species. For the rest, we know their DNA barcodes, but we have no library to match them to.

Southwest Western Australia has a huge diversity of mycorrhizal fungi, which is probably greater than any other part of the globe. Much of this diversity lies beneath our feet, and most of us would therefore be unaware of this biodiversity treasure.

Project partners and collaborators

Janine Kuehs

Leonie Valentine

Anna Hopkins

Bonnie Beal Richardson

City of Mandurah

Shire of Mundaring

What you can do

Quenda have persisted in and around cities across southwest Western Australia. They appear to be resilient little critters, but we can help them too:

Predation has been identified as a major cause of mortality in quenda [8]. Pest animal control (e.g., fox and feral pig baiting, control of domestic cats) is therefore required in many urban reserves to protect these vulnerable native species. Semi-permeable fencing around reserves could help to prevent domestic dogs from entering urban reserves, while leaving gaps small enough for quenda to pass through.

Quenda generally avoid parks and reserves where dogs are present. Keeping your dog on a lead will help quenda there [9] – even if your dog does not attack quenda, if they are disturbed while they are sleeping, quenda will move away from cover, increasing their exposure and risk to other animals or being hit by cars.

Quenda visit many people’s backyards [10]. Quenda diggings across our lawns are valuable aeration of the soil, increasing water infiltration [2, 6]. As an added bonus, the animals are probably digging out beetle grubs that would otherwise damage the roots of lawn.

Quenda prefer gardens with more vegetation in them [10]. We can therefore improve the habitat quality of our backyards as well as urban reserves to maintain and potentially increase quenda populations. Planting with dense bushes – such as Acacia lasiocarpa or Calothamnus quadrifidus, which provide protection from predators – would help improve habitat for quenda and other native wildlife.

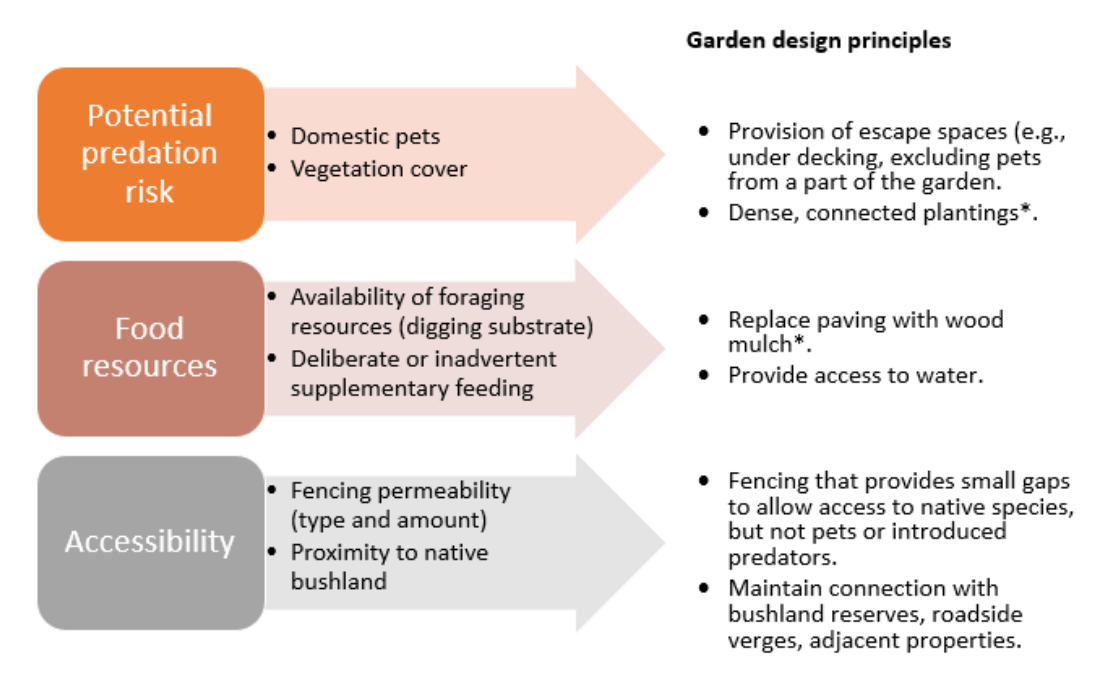

Design principles to provide habitat opportunities for bandicoots, and potentially also other wildlife, in residential gardens [10].

Funding

Western Australian State Government; Centre of Excellence for Climate Change, Woodland and Forest Health

Project duration

2016 - Ongoing

Read more about this work

1. Valentine, L.E., et al., Bioturbation by bandicoots facilitates seedling growth by altering soil properties. Functional Ecology, 2018. 32: p. 2138-2148.

2. Valentine, L.E., et al., Scratching beneath the surface: Bandicoot bioturbation contributes to ecosystem processes. Austral Ecology, 2017. 42: p. 265-276.

Lead researchers

Areas of research

Conservation

Lead researchers

Trish Fleming

Wildlife Conservation, Harry Butler Institute

View staff profile

Amanda Kristancic

Adjunct - Harry Butler Institute, Murdoch University

View staff profile

Shannon Dundas

Adjunct - Harry Butler Institute, Murdoch University

View staff profile

Gillian Bryant

Adjunct - Harry Butler Institute, Murdoch University

View staff profile

Catherine Baudains

Adjunct - Harry Butler Institute, Murdoch University

View staff profile

Giles Hardy

Emeritus Professor - Harry Butler Institute, Murdoch University

View staff profile