Blog

Interview with Dr Brenda L Croft

.tmb-960-banner.png?Culture=en&sfvrsn=43c33e6d_1)

Dr Brenda L Croft is from the Gurindji/Malngin/Mudburra peoples from the Victoria River region of the Northern Territory of Australia, and Anglo-Australian/ Chinese/German/Irish/Scottish heritage. She is Professor of Indigenous Art History & Curatorship at the Australian National University (ANU) and a co-team leader of the ANU's "Murrudha: Sovereign walks – tracking cultural actions through art, Country, language and music" initiative.

Brenda's multidisciplinary creative-led research encompasses Critical Indigenous Performative Collaborative Autoethnography and Storywork methodologies and theories. Brenda has a long-standing engagement with her patrilineal family and community members, both on traditional homelands, and with dispossessed Gurindji-affiliated communities.

Brenda L Croft is an artist of four decades standing. Her work is represented in major public collections in Australia overseas and in private collections, and she has exhibited in major exhibitions and cultural events in Australia and overseas. In 2024, Brenda was the Gough Whitlam and Malcolm Fraser Visiting Chair of Australian Studies at Harvard University in the US. Here at Murdoch University, we are fortunate to have artwork from two of her important series in our art collection.

I spoke to Brenda at campus in May 2025 when she paid us a visit to see the Murdoch University Art Gallery exhibition, Speaking Truth to Power, Contemporary First Nations Art from the Murdoch University Collection. Brenda was in Perth visiting the Bernt Museum at University of Western Australia (UWA) as part of a contingent from her patrilineal Gurindji community in the Northern Territory. After a decade’s activism, the group had finally been able to access field notes from the 1940s that were collected from Jinparrak (2nd Wave Hill Station)and Limbunya regions, by anthropologists Ronald and Catherine Berndt. The visit was facilitated by Associate Professor, Stephen Gilchrist, Director of the Berndt Museum.

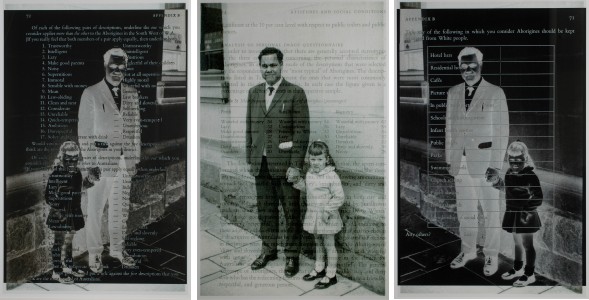

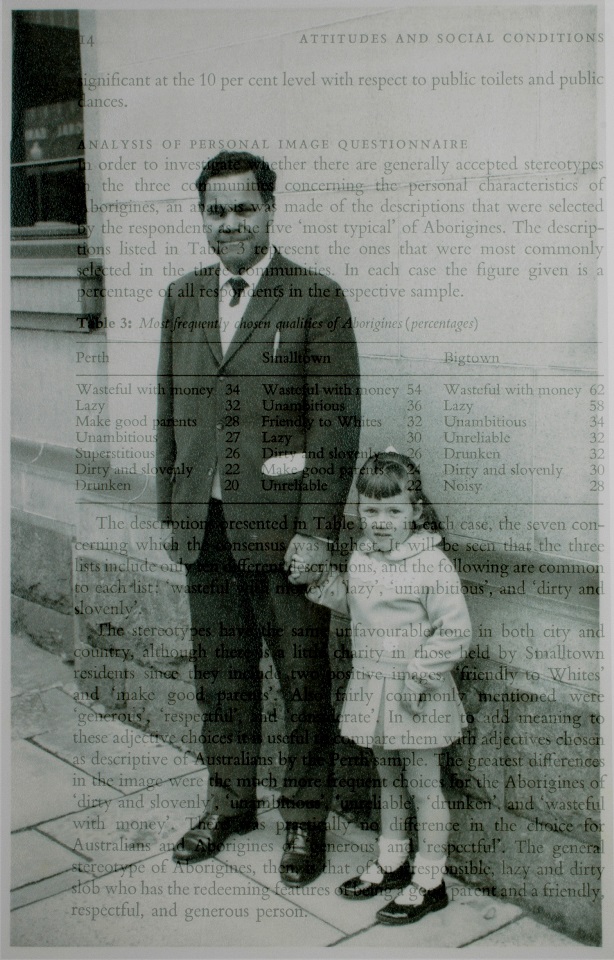

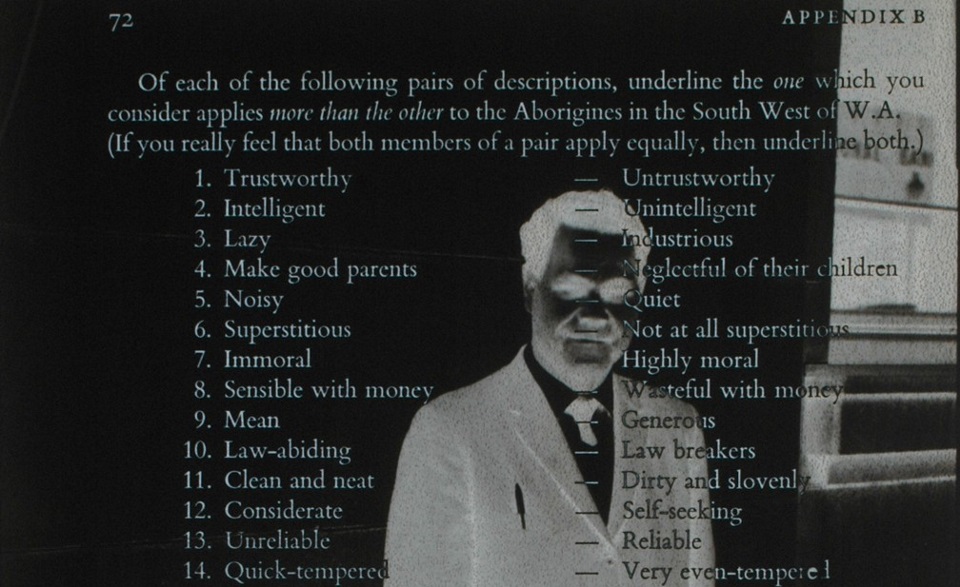

Speaking Truth to Power includes three of Brenda’s photomedia works, Trustworthy Difference, Analysis of Personal Image, and Hotel Bars Exclusion, from the series ‘Peripheral Vision’, created in 2005. We took a walk around Murdoch campus and finished on the fourth floor of Building 450, to see one of her other earlier works, west/ward/bound (1999) where it hangs on public display just down from my office.

After our walk, we sat down to talk.

Josephine Wilson

Murdoch University Art Collection Board member and English & Creative Arts Lecturer

Brenda:

My name is Brenda L Croft. I'm a Gurindji/Malngin/Mudburra Chinese, Irish, Scottish woman on my father's side of the family and Anglo German Irish on my mother's side. And I would also like to start by paying my deep respects to the traditional custodians of this place, Whadjuk Country, in the Southwest of the continent. Saying that has deep meaning for me as a visitor to this country, both as a First Nations woman and as a person who has grown up in Australia, because I was born here, nearly 61 years ago, after my parents had come to this part of the country as newlyweds, for my father's work.

I always think of Perth and this place, Whadjuk country, as a little bit like home because my earliest memories come from here. When you are a displaced First Nations person as an outcome of the ongoing settler colonial project, you have lots of places where you work out what is home, and for me this is one of those places. So, it's a privilege to be back here and a privilege to be able to come visit Murdoch University while I am in Perth at the Berndt Museum. You know, we've had a decade long fight to access those field notes, and the embargo was finally lifted last year. Two days ago, I met with dear colleagues now at the Berndt Museum, and with First Nation colleagues, some associated with UWA. It was very, very moving, and we all said that we've come here with sorrow, because many of our elders have passed away in the intervening ten years, but we're also here from a sense of optimism and positivity about what we can do to ensure that those field notes are available for future generations.

Josephine:

Thank you, Brenda. I want to return to a couple of the points you've raised: you acknowledge that people, place and context are extremely important, not just for Indigenous peoples, but also for white people such as myself. I see this expressed through your artwork, with great subtlety. The works that we see in the Murdoch University Art Gallery exhibition, and on our walls and corridors, come from different periods of your work. Earlier works from the west/ward/bound series are displayed in the corridor outside my office in Building 450.

You are an artist who acknowledges the significance of the trace, of memory, and the importance of the archive, even if that archive is incomplete, partial, and constructed through a colonial lens. Can you tell me how you became interested in documents, both personal and public, and how you first came to use those in your earliest digital work with image and text?

Brenda:

I started to work in the digital sphere way back in 1998. A dear friend and colleague of ours, Derek Kreckler, was at Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts (WAAPA) and he organised a residency for me, because I wanted to learn how to use Adobe Photoshop. That led to then coming back here in 1999 to work at the Art Gallery of Western Australia (as Curator of Indigenous Art).

I think back to those previous iterations now. I guess I've just always accessed family archives and that would be through my mother and father's love of slide nights. In my generation, you'll hear lots of artists who work in photomedia talk about that. We'd have the slide night where we'd put up a sheet, in the kitchen usually, and no matter how many times I saw those slides, I never tired of it. I My brothers don't remember this because they were younger than me and got more into TV, and things like that. But I loved these slide nights and going through the old photo albums.

And I think subliminally this was because there was so little visual material about my dad, which triggered the question: Why is this so much material on my mum’s side of the family but not on my dad's? And it was because he was a member of the Stolen Generations; he was born on his traditional country in 1925 in the Northern Territory, on a cattle station (Victoria River Downs, Old Moolooloo Outstation). He and my grandmother, who was Aboriginal/Chinese, were taken away from that country under the policies of the time. I was recently finding out information about the lone Mounted policeman, Constable Hemmings. I had been researching the Timber Creek Police Letter Books from that period, and Hemmings comes across as a very humane person doing his best. He was the only policeman out there, in remote part of the Northern Territory, writing out of frustration to the powers up in Darwin, about sending supplies, food and other essential for people under his jurisdiction for whom he felt responsible.

There is much more to be discovered about him, but it’s been interesting to see myself warming to him. My grandmother and my father, who was an infant, were taken somewhere that was considered by the people who went there as a place of incarceration but was a place where they were safer than where they were on that station. I’ve gone off in a little bit of a sidetrack. but it was the lack of material on dad's side that brought me to the archives. They were something that I was just always intrigued by.

Above left to right: Brenda L. Croft - Trustworthy (difference), Analysis of personal image, Hotels Bars (exclusion), 2005, Giclée prints from the series Peripheral Vision. Murdoch University Art Collection.

The visual image, for me, was about looking for myself, looking for traces in those images, because I had a very fair-skinned, blonde, blue-eyed mother and a very dark stereotypical-looking Aboriginal father and I was trying, I think, from a very early age to work out where I could fit into this kind of space. So, for me, there was always the interest in family history. We were a long way from home in terms of my mother's family, who were way over in the Eastern States. I think she felt very isolated over here in Perth, in the early 1960s, being a young white woman married to an Aboriginal man in Perth.

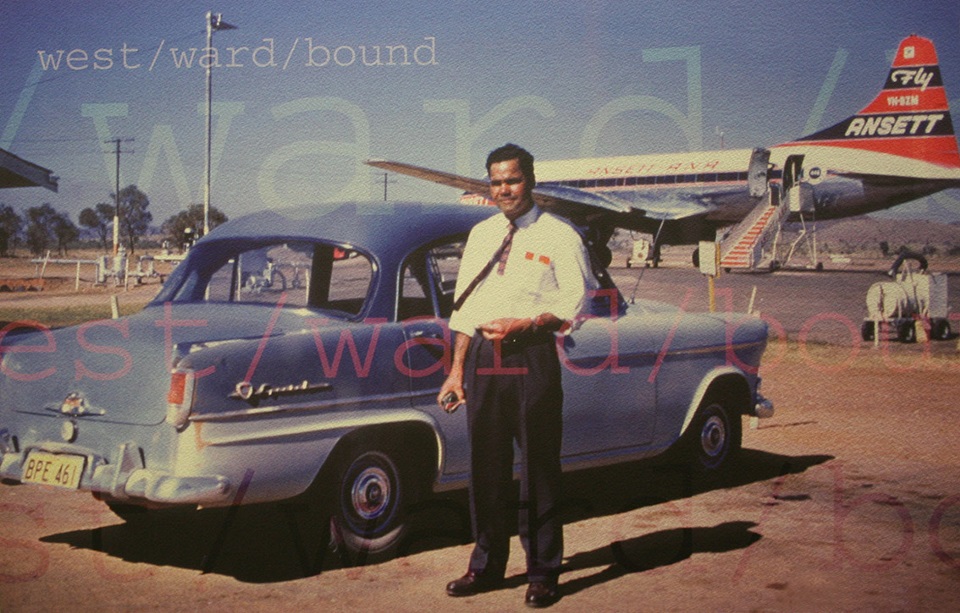

Above: Dr Brenda L. Croft – Arrival, 1999, Giclée print from the series west/ward/bound. Gift of the artist 2012. Murdoch University Art Collection.

I've interviewed the neighbours who were in the street where my parents lived in Dianella. And in 2017 when I was visiting Perth, I interviewed the people who'd built the first house (in the street at Dianella) and were still living there - the Smiths. They were just lovely. They remembered my parents and were really beautiful, warm people. My dad was working on the railways here as surveyor, and Dianella was a kind of bush suburb. There was lots of white sand; it wasn't built up like it is now. But my Mum always talked about how she missed her family, and how she felt she felt very much under observation here, wondering if she was doing the right thing having married ‘outside of her station’, if you like.

Josephine:

That kind of childhood experience obviously informs your practice now. It's not just personal, is it? It's also political.

Brenda:

Absolutely.

My body is my archive. I am the archive

Josephine:

In your excellent PhD you talk about the transformation of the personal into the political through your work in the archives - and I’m calling them the archives very generally. We usually think of archives as public and institutional, like State archives and Government collections. In your work. I can tangibly see the transformation of material through the personal into the political (and back). For me, your work is representative of something that is both very Brenda Croft, perhaps because I have known you for a long time, and also representative of a particular historical moment in the story of Australia and Stolen Generations. I came to Australia from England in 1966 as a small child, to the North-West. I don't remember it ever being said, (because it didn’t have to be) but there was an unquestioned and dominant idea of the ‘real’ Aboriginal person. And that idea has been promulgated by white Australia and is evidence of white Australia's failure to speak with clarity and truth about the complexity of what happened to Aboriginal people when they were forcibly removed, and the effects of that removal. And we know that the erasure and the loss is profound and that it continues. So, Brenda, do you see yourself working to redress these issues, to critique them, or is your drive foremost a personal one? I guess I'm interested in that question of you as an artist, and the way you pursue personhood. You talk so much about your family. Is that at the core?

Brenda:

It’s all those things. My work is very much about embodiment. My body is my archive. I am the archive. And my story is absolutely related to me personally, but it clearly has resonance for other people who've had similar experiences.

My mother made sure that you leave a trail

I don't know if humble is the right word, but I am really happy for it to be a way a doorway for other people, for other artists to be making their work. I did a creative-led doctoral research project, which comprised a collaborative exhibition with family and community up home and also displaced Gurindji community members.

My mother made sure that you leave a trail, and because she was so determined to find those missing pieces for my father, she understood how important it was. I'm very, very grateful to my mother's family for embracing my father. They really adored and loved him, and he was very much made to feel welcome. But my mother was very aware of the question, Where's your family? She said, Let me help try and track them down. And she was determined to do that. I learned by watching her.

She organised for us to go to Darwin in 1974, to meet my grandmother, my dad's mum, who was terminally ill and didn't want to go to hospital. We had sold the family newsagency, so there was a little bit of money to be able to get all of us up there. It was 1974, and I was 10. I have very clear memories of her presence, and that included her scent, the way she spoke to me in Aboriginal Kriol. I carried that with me for many years. We only spent three weeks with her, and she died later that year. I talked to my brother who was three - a lot younger than me - and he couldn’t remember her, only elements of where we stayed. We were at the Retta Dixon Children's Home, where my grandmother was resident. It is an infamous place, that came after the Kahlin Compound. My grandmother was beloved by all the kids who were there, many of whom were my cousins. It was run by the Aboriginal Inland Mission. A Mr Pattemore - I can't remember his first name - organised for my family to stay there to meet my grandmother. And then shortly after that in December, just after my grandma died, Cyclone Tracy hit Darwin and wiped out the home.

I have clear memories of being with her. My mother was very dogged and determined to help my father track down family. I've been fortunate in that sense, as it’s just always been part of my life. And I know that my story and journey are not the same for everybody… I've worked with wonderful people over here in Western Australia.

A dear friend of mine is the artist Sandra Hill. Sandra went through Sister Kate’s. I spent time in Sister Kate's as a kid, as a child. My mother had mental health issues. She had a breakdown when she was over here, from being so isolated, I think. She and my dad had split up (briefly). He didn't know how to deal with someone who had mental health issues, so my mum put me in sister Kate's (for respite), and my earliest memory is of being in a dormitory. For years I could not work out where this memory came from, until I spoke to my grandmother about it years later.

-(002).jpg?sfvrsn=31a1f6b3_1)

Above: Sandra Hill - Homemaker # 7 (Cake Making), 2012, oil on canvas. Murdoch University Art Collection.

I was in a dormitory full of children in cots, and I was the only kid who was awake. I was standing in my cot looking out the window at a streetlight, and I'm clearly wondering where my parents are. I was only in there for about six weeks.

And years later, I was thinking, why do I keep having this vision of being surrounded by all these kids? I remember at childcare, you had to have an afternoon sleep. I just wouldn't go to sleep. I've always been a light sleeper, I think because of that. I'd be the only kid who was awake at the childcare or preschool. So those memory traces are always there. I take a lot of inspiration from people like Toni Morrison. She has written about having to recreate memories that maybe never existed. They're the fragments of memory that you want to pull together to create imaginatively.

It is a kind of literary archaeology: on the basis of some information and a little bit of guesswork you journey to a site to see what remains were left behind and to reconstruct the world that these remains imply. [1]

Josephine:

So, you have to flesh out those spaces? In your discussion of making your work you write, ‘I become the site of excavation’. This is a wonderful image of the material labour of memory; it isn’t just, Oh, here is my memory; it's the extraction of that memory, and as you say, the reconstruction.

Brenda:

People now talk so much more about genetic memory. There’s blood memory. Like that image of dad from west/ward/bound, the series that you referred to earlier?

Josephine:

The one of your father where he's standing in front of the car?

Brenda:

The two-tone Holden.

Josephine:

It's fabulous. On a sort of dusty runway like you could have found in rural regional Australia at certain times. Behind is the Ansett plane. The blue sky and the blue of the car.

Brenda:

The mountain and range. It is Outback, but it's also universally “Australian”: here is the Holden; here is the Ansett plane; here is the handsome young man - except he's black. He's clearly Aboriginal. And he's got lovely-creased trousers. He is dressed very beautifully.

Above: Dr Brenda L. Croft – west/ward/bound, 1999, Giclée print from the series west/ward/bound. Gift of the artist 2012. Murdoch University Art Collection.

Josephine:

A handsome..

Brenda:

A very handsome man. This is Queensland in 1960, and that is not how you expected to see Aboriginal people represented. He was working at the time as a surveyor on the railway line (from Townsville to Mt Isa), helping relay the (standard) gauge from Townsville to Mount Isa. And the person taking the photograph - the trace is there as well – that is my mother. My mother and father had met a year earlier on the Snowy Mountains scheme, where he was working as a surveyor. It was one of her first jobs, I think, away from home. And she had gone down to the Snowy to work as what you’d now call the Personal Assistant for the second in charge, who she loved. She really had a beautiful boss. My mother was a gun stenographer, shorthand writer, and typist. She met my father on her first night, at a dance to raise money for the families of three men who'd been killed earlier that week in an accident in the tunnels. There was a saying at the time that for every mile of tunnel built, a life was lost. It was very dangerous work. My dad was above ground - he was a surveyor. So, they met at this dance.

I think she had three marriage proposals that night because the number of men to women was very disproportionate. So, if you were a single woman turning up -

Josephine:

You were doing well.

Brenda:

Yeah. And there was lots of ‘New Australians’. I have always loved this idea of a ‘New’ Australian, an ‘Old ‘Australian, you know? What was my dad? How did he fit into all of that? He and my mother met there, and then they had quite a tumultuous relationship, but not from my dad. My dad was the most patient, gentle person you could ever meet, without a skerrick of bitterness in his body, which always amazed me because of what he had experienced in his life. He was the most open, loving, generous, welcoming person you could meet. I was talking to Uncle Richard Walley - I've known Richard since I was young through our work in the creative arts sector. He shared a story with me I'd never known. He said, Oh, your father used to bring David Gulpilil to here over to Perth in the ‘70s. He worked as David Gulpilil’s manager for a while, when Dad was at the Department of Aboriginal Affairs, so he worked with the Ramingining Dancers. And I had known that Dad came over here when the Indian Arts Festival was on in the1970s, when Richard was a very young man working with a dance group. He said, Oh, your dad, we loved being around him. He was such a gentleman, and he always treated us with dignity and respect even though we were young. It was just a lovely moment, Richard and I talking about that. And here we are all these years later.

My parents relationship was tumultuous mainly because my mother was dealing with (being) bipolar, and nobody was diagnosed in those days. Nobody knew what it was. She was a very smart woman…and for lots of women of that particular era who were smart there were very few options: you got married; you had kids. What did you do if you had a brain as well? She was a great creative writer, but she would have these turns.

Josephine:

You said she was a maker?

Brenda:

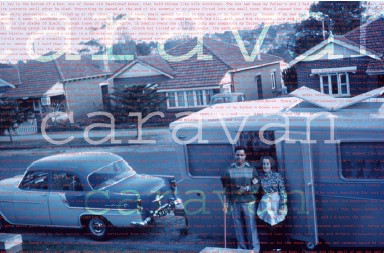

She was a maker. She was an amazing sewer. She could do millinery, woodwork. I've still got her a beautiful bookshelf she made. I've got a bedside lamp she made, foot stools…And so when I sit in my lounge room with my feet on the stool that my mum made, I feel like I'm with my mum. And her handwriting is under underneath it too, which I love. She always wrote, Joe Croft, Perth to Kyogle, which is where we moved after we left Perth. I can't get rid of these things, because my mother's handwriting is on them - or my dad's handwriting. But they split up [back then], and he went to work in Queensland on the railways. He helped relay the line from Townsville to Mount Isa, and this was their reconciliation, if you like,

Josephine:

This is the origins of that moment.

Brenda:

It’s exactly captured there. She's just gotten off the plane, and she takes this photograph of my father. And I said to him - because I drilled him: How come you and mum got back together? He said, Well, she wrote to me, and she sounded very happy. And I said, why don't you come up for a holiday? And so then led to them getting engaged and married (in 1962). There's another photograph that he took of her (at the same time and place), which I've used in later work (Made in Australia series, 2018). In 2018 I did an exhibition on my Mum in honour of would have been her eightieth birthday in 2018, and I used the slide for that in a slightly different configuration. But you can see there's this young love.

Above: Dr Brenda L. Croft – Caravan, 1999, Giclée print from the series west/ward/bound. Gift of the artist 2012. Murdoch University Art Collection.

It was a love match. I mean, he clearly loved her, even with all the difficulties. That was good for me to understand, because I only saw the kind of fights that were later when she was really struggling with mental health issues. But he looks happy and proud to be able to drive her around to show her places.

Josephine:

You can view the west/ward/bound series on public display at Murdoch University campus, Building 450, Level 4. Beautiful work. Your other artworks featured in the Speaking Truth to Powerexhibition at Murdoch University Art Gallery, are artworks which, perhaps offers more sense of the force of not so much the personal and of love, but rather of the institutional, the bureaucratic and the public. It is an artwork which uses layered imagery including census documents. Is that what they are, Brenda?

Brenda:

Surveys and the census. The gathering of information.

Josephine:

There's something indelibly powerful about the use of documents in your work, Brenda. They have such a force for me. And it's not just those original documents they were printed in text and are a certain way different to the digital. It that when you see on that work, you see the questions. Can you talk about where how that work evolved for you? And about the relationship between text and image in that work and how they speak to or against each other?

Brenda:

Well, there's multiple layers with that triptych. It’s from a series called Peripheral Vision (2005). I created it when I was back in Sydney, but I fist exhibted them in Perth at Artplace Gallery. The images are very specific to this place, to Perth, because the image was taken by the Forrest Place street photographer, who was an unknown person. Many people in Perth in the ‘60s will have photographs taken by the photographer who worked in Forrest Place. You dressed up to go to town. You go to town, and you'd be walking through, and you'd be asked, Would you like your photograph taken? Then you could go to…is it London Court? And you could order prints, so, my Dad clearly had done that later.

Above: Dr Brenda L. Croft - Analysis of personal image, Hotels Bars (exclusion), 2005, Giclée print from the series Peripheral Vision. Murdoch University Art Collection.

My father and I were on our way to visit my mother and my new, fresh baby brother Lindsay, at St John of God Hospital in Subiaco. So, my brother had just been born. So, I'm three years and a few months old. You can see I'm wearing a beautiful outfit that my mother had sewn. I can still see the colour: it was a like an olive green. Oh, so lovely. A pale green wool suit. It's August, because he was born on the August 6, so it's a short time after that. I've got little white socks and shiny black patent leather shoes. My hair has been done beautifully. I don't know if Dad did that.

I’m going to be having lunch with my cousin (later in the day of this interview), and I will try and clarify that. I often spent time with her family from my mum's side, who lived over here – they were my mum's only family on this side of the country. So, there I am: I am beautifully dressed, and I am holding tight to my dad's hand. And he looks a little bit tired. He'd probably been at the hospital with my Mum and come home to get me. I was probably staying with Auntie Pat, actually. And he's beautifully dressed in a suit, and I'm holding his hand. And I look a bit reticent. I'm looking at the photographer. I do know that when Dad was walking around with me through Perth he was stopped and asked for identification, to show that I was actually his daughter. I don't know if it was that day. The photographer hadn't done that, but somebody else. You were constantly under observation. And he was clearly much darker than me. And this is something that used to happen with him and my brothers, my youngers brothers were blonde-haired and the youngest was blue-eyed.

When we flew up to Darwin in 1974, I wondered why us three children were taken up into the cockpit to watch the pilots flying the plane. I thought, Why are we up here and nobody else? Well, it was because the air hostess had asked my dad for ID for my brothers to prove that they were his children. My mother and I were sitting on the other side of the aisle, and she, being my mum, had ripped into the poor air hostess. And so, to kind of cover up for that, they'd said, Oh, we will take the children to the cockpit. So, we had this special excursion. But my dad had been asked for identification to prove that I was his child; so maybe that is there somehow in this image. Maybe I was a bit shy?

Above: Dr Brenda L. Croft – Detail of Trustworthy (difference), 2005, Giclée print from the series Peripheral Vision. Murdoch University Art Collection.

But overlaid here is text from a social sciences book. I collected all these books. They were produced through the University of Sydney, under a Myer Social Research Foundation grant. There is one from each state and territory, and this one relates to Perth and WA. It’s from the 1960s. It surveys the attitudes of people in this part of the country. These surveys are fascinating. They don't give the actual location of places; they call a place, Big Town, Small Town, Regional. And so Big Town is clearly Perth. And even though these are generic questions, would you live next door to an Aboriginal person; would you live next door to a part-Aboriginal person? And then it had this weird demarcation through migrants; different migrant groups were considered less acceptable. You could pick and tick various boxes as to how you would respond to that. Do you think Aboriginal people should be allowed to go to the local swimming pool? Part Aboriginal? Dutch people? German people? This is not too far after World War Two, so there would have been an influx of new migrants. Do you think Aboriginal people should be allowed to go to a hospital? And here we are, on the way to the hospital. So, there's all these kinds of things and they are very bland. What is it called? The banality of evil, Hannah Arendt's statement about how it's just the everyday, which is what we're seeing now in politics around the world. And for me, having just come back from a year being based at Harvard University, which I loved, I just watch in sadness and horror at the daily goings on over there. I am keeping in touch with friends and colleagues who are coming from a similar, Indigenous background, or People of Colour, or women, or whatever, you're just going, Oh my god. They know that when we accept things, when we don't speak up, when we don't challenge, we become complicit.

I like to use things that look like the everyday: Here's the street photograph. Many people in Perth will have something similar in their own archives. Here's these surveys. If you read through the text, you realise how offensive it is. But this is what my parents had to deal with every day. And the power of it is that it originates from the apparently subjective – sorry - objective world of data collection and bureaucratic management, which is, as science says, ‘simply collecting’. Simply collecting! It’s really important that all of us who are critically engaging to ask questions of those sorts of documents. And anybody who's gone to the library, say, the Battye library, or into any collections of old education books will just go, Oh my god. They they're so important to remind ourselves that this is not very long ago.

Josephine:

I grew up in that period where, the Grade four or five English Social Studies book had Aboriginal people dying out.

Brenda:

I've got really dear colleagues from Tasmania, and they had been told that they didn't even exist anymore, that they died out in the 1800s. As a researcher who uses my own body and experience as the vessel that carries that research, I've always been aware of the traces. It's not so much what has been erased; It's what is there that we can't physically see. The embodied kind of relationship to it. And you think about that even as a visitor.

Richard Walley eloquently talked about that; he took us down to the river's edge to Derbal Yerrigan and spoke in language and welcomed us and talked about songlines that went all the way up through to Gurindji country.

Whilst at Murdoch University campus I was climbing into the garden on the way up here (to meet Josephine) to look at a beautiful plant. It was a Eucalyptus Macrocarpa. I like to I remember the plants that are here.

The kangaroo paw has always been one of my favourite plants. I have some in my garden in Canberra. I came back in 1994 for the Dangerous Relations conference that (then Director) Sarah Miller organised at Perth Institute of Contemporary Art. I went out to the family house in Dianella and in the garden were all the roses that my father had planted back in the early 1960s. I've still got the exercise book where he's laid out which roses went where. So, I knocked on the door, and a woman answered the door. I said, I’m sorry. I'm prowling around in your garden taking photographs, but my parents built this house.

And she just said, Oh, you're the Croft girl. She'd bought it off them and she took me through and showed me the house. She was just lovely. And then I went there again in 2017, and all the garden had been dug up, but the house was still there, and so I knocked on the door again. They were a gorgeous young couple from Melbourne. They were Indian and Chinese, and his parents were there. They'd taken the house back to its original beautiful jarrah floors. I introduced myself, and they took me through on a guided tour of the house. I think they've moved back to Melbourne, but I invited them to an exhibition at Art Gallery of West Australia that Carly Lane curated which included my 1998 series ‘In my mother’s garden’. It had photographs of my family's house from the 1960s, but also ones that I'd done in 1998. And I gave them one of their/our house.

Josephine:

That's beautiful.

Brenda:

And so, it's those kinds of traces. We don't know what's there. I love the bore water, the iron bore water.

Josephine:

The suburban palette.

Brenda:

It's like blood seeping up from the ground, you know? And you can't get rid of it; it returns and returns. People were always complaining about the bore water. I love it. Iron ore is what has given this place its wealth… That kind of tension that always exists wherever you are. I feel that when I'm walking in Sydney. I feel that when I'm in Canberra. And, you know, I have a responsibility as a First Nations person to work with local people who are the custodians of the land on which I'm visiting or working. I can't just walk through some place and take. I can't just be another extractor. I have to be doing something that is addressing what's happened on a place and provide space for people who've allowed me to come and visit. Those things are always in your head, as a First Nations person, when you're traveling around this continent.

Josephine:

And which is such a different position to the fantasy of the sort of globalised sort of intellectual, if you like, that was a kind of figure that dominated European ideas.

Brenda:

The flaneur.

Josephine:

The flaneur moving seamlessly from here to there, much like a colonial manager. Yes. Speaking the same language wherever you went.

Brenda:

Well, that's right. You know, Harvard came out of being a college for Christian and Indian youth - ‘The Harvard Charter’. That's how they got their building money from the churches in England back in the 1600s, because they were educating Native American youth. Being in Harvard and walking around that kind of venerated campus you're really aware of the Massachusetts People whose land that's built on… There's still a huge community of Wampanoag people from Aquinnah up at Noepe, or what's now called Martha's Vineyard. I took my son up there. People have been living on their country for thousands of years. They're not all down the rich white end of the island; they live on the Northwest, and they've always been there. I was meeting up with other Massachusetts mob and making sure they were involved in the symposium I was organising. I said, I want a critical density of bodies on this campus, of Indigenous people, and People of Colour to talk about these issues…because it's a place that is so white, and it's so moneyed.

Josephine:

I can't imagine what it's like.

Brenda:

Its money comes from its endowment, which comes from slavery. They have a reckoning of their own, dealing with that. But prior to African American slavery, there was Native American slavery. There are these tensions, and we can see with what's happening with the people protesting about what's happening in Gaza… I was watching all of this while I was there, and I was mindful that they're meant to be places of protest….

We're in a very jaw-dropping place. Every day is a kind of new reveal of another dreadful act of dispossession; you know, what's happening to people being taken, and citizens being disappeared into gaols in El Salvador. We are all outraged, but we have we also have our own outrages here in Australia.

Josephine:

Yes. I want to thank you very much, Brenda Croft, for coming and talking to us. And I'm hoping that we can orchestrate some means by which we can have more of you and your knowledge and generosity on campus, and learn from your work as an academic, an activist, and an artist. You are incredibly generous, and there are so many reasons why one might not be generous, having legacies that are violent and terrible. And I thank you for your words and your work, and for coming to Murdoch University campus.

Brenda:

Thank you, Josephine. I try and live by my father's openness. to be like him. My mother's anger sometimes rises up, so I just channel both when I need to. But he was open, and I try and refrain from that (anger). Because as human beings we believe in humanity, you know? And that's what I say to people: it's about caring about other human beings and treating people as you wish to be treated.

Josephine:

Thank you, Brenda. Thank you so much.

Feature image: Dr Brenda L. Croft - Jamie Kidston/ANU.

[1] Toni Morrison, “The Site of Memory” in William Zinsser Ed. Inventing the Truth: The Art and Craft of Memoir. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1987, 103-124.

Blog

Interview with Dr Brenda L Croft

Posted on

Wednesday 22 October 2025

Topics