Professor Rajeev Varshney is a pioneer in agricultural science, specialising in genomics, genetics, trait discovery and molecular breeding. This is how he rose to the top.

It’s said that you should never meet your heroes, lest they disappoint.

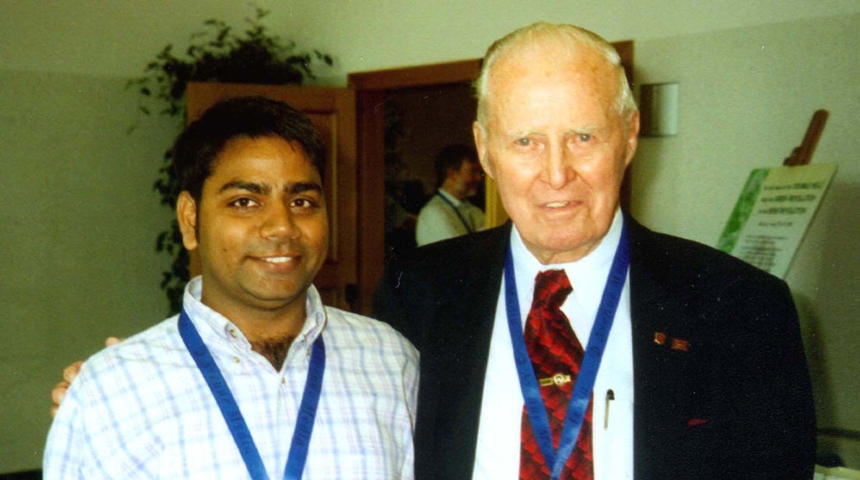

But meeting Norman Borlaug - the father of the “green revolution” and 1970 Nobel Prize winner for his lifetime’s work reducing world hunger – inspired in Professor Rajeev Varshney a career pivot and determination to help some of the world’s poorest farmers.

Professor Varshney was a young agricultural scientist working in Germany on a project to improve the malting quality of barley when he travelled to a scientific conference in Italy. The year was 2003 and the ground-breaking Human Genome Project, which sequenced and mapped all genes in human DNA, had just concluded after 13 years of intensive international research effort.

Like humans, plants have genes that influence height, colour, and resilience – or vulnerability - to disease. Agricultural genomics involves the study and classification of these genes, allowing scientists to combine desirable traits to boost crop productivity.

Dr Borlaug was a keynote speaker at the conference, and he called on the scientists assembled there to harness the transformative potential of genomics to relieve hunger and malnutrition around the world.

Image: Professor Varshney with Nobel Prize winner Dr Norman Borlaug at a conference in Bologna, Italy, in 2003

Image: Professor Varshney with Nobel Prize winner Dr Norman Borlaug at a conference in Bologna, Italy, in 2003

“I challenge the next generation of scientists to use these new tools and techniques to address the problems that plague the world’s poor,” he said.

Professor Varshney explains, “these words inspired me. I went back to Germany and tried to find ways and devise approaches for genomics-assisted breeding and how it could enhance crop productivity and improve food security using less resources – water, land, pesticides and fertiliser - especially in developing countries.”

Dr Borlaug’s words resonated strongly with Professor Varshney because he had grown up in Bahjoi, a small town in Uttar Pradesh in northern India, and witnessed the battles faced by smallholder farmers in his home state cultivating crops in the face of drought, disease, a changing climate and degraded soils.

“These are farmers who have only one to two hectares. They need to produce for themselves, and the thing is when they grow these crops, the productivity is not very high,” Professor Varshney said.

“I thought, how can we develop better varieties which can enhance crop productivity so these farmers get more surplus, so they can make more money and they can also use this money to send their children to school?”

Discovering a love of learning

The irony of such a thought wasn’t lost on Professor Varshney, who’s passion for formal learning had not always been evident. As a child, he constantly ran away from school.

“I didn’t want to be there and so I’d sneak home or find younger kids to play with. Eventually, my parents hired a tutor, but I would run away and hide under the bed to get away from him.”

It was only when school literally came to Professor Varshney – with the founders of a new school in his town needing classroom space and leasing a few rooms in his uncle’s home – that he was finally forced to knuckle down and commit to learning.

“My father said: ‘Now the school is in the house, what can you do?’ By this time, I was already quite a grown-up kid. The teachers interviewed me and asked me several questions and somehow, I knew quite a lot. They said to my parents: ‘You told us he is a naughty boy, but he is a very capable boy’.”

From that moment, Professor Varshney embraced learning and after a flirtation with cosmology, settled on agricultural science for his future career.

From school, he completed his Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in Botany at Aligarh Muslim University. He then joined the laboratory of Professor PK Gupta at Chaudhary Charan Singh University and completed his PhD in Agriculture.

From there, he joined the laboratory of Professor Andreas Graner at the Leibniz Institute of Plant Genetics and Crop Research in Germany for five years, before moving to the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) back in India.

Building global partnerships

ICRISAT is a non-profit scientific research organisation with a focus on building global partnerships – something Professor Varshney, with his ready laugh, warmth and collegiality – has a real knack for.

“When I joined ICRISAT in 2005, I planned to develop genomics resources and integrate them in crop improvement in developing countries.”

To achieve this goal, Professor Varshney – together with senior leaders at ICRISAT and in collaboration with Department of Biotechnology, Government of India – established the Centre of Excellence in Genomics in 2007, rebranded in 2017 as the Centre of Excellence in Genomics and Systems Biology.

Through this centre, he collaborated with colleagues in Australia, Africa, Asia, and North America and developed a network of more than 140 organisations in more than 35 countries across six continents.

Image: Professor Varshney in Niamey, Niger, with a local business entrepreneur holding a pearl millet hybrid in 2018.

Image: Professor Varshney in Niamey, Niger, with a local business entrepreneur holding a pearl millet hybrid in 2018.

During his time at ICRISAT, Professor Varshney mapped the genome of more than a dozen “orphan tropical crops” including chickpea, pigeonpea, peanut, and pearl millet grown by smallholder farmers in many parts of Africa and Asia. While these crops generally don’t enjoy a high profile in the Western world, they are critical to smallholder farmers, providing food security and generating income.

One flagship project was funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The US$67 million Tropical Legumes project led to the development of 266 legume varieties and production of almost 500,000 tonnes of certified seed.

This seed was planted in around 5 million hectares that benefitted more than 25 million people in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, producing 6.1 million tonnes of grain with an estimated value of US$3.2 billion.

Image: Professor Varshney led the Tropical Legumes Project, funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Here he is with the man himself at his home in Seattle in 2012.

Image: Professor Varshney led the Tropical Legumes Project, funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Here he is with the man himself at his home in Seattle in 2012.

Moving to Murdoch

With these impressive projects behind him, Professor Varshney was ready for a new challenge in a new country, and earlier this year, he moved to Perth with his wife Monika and daughter Preksha. Preksha is a Year 8 student at Corpus Christi College, while his son, Prakhar, is studying human rights law at Kings College in London.

“In moving to Murdoch, I was looking for new challenges with a university that has translational research as its heart,” he said.

Professor Varshney said feeding an estimated global population of 10 billion people by 2050 would require sustainable production of food using less land, less water, fewer pesticides and fertilisers – all while adjusting to the vagaries of climate change. At the same time, the food produced would need to be nutritionally rich to support population health in the face of global pandemics and other emerging health challenges.

“The pandemic and war in Ukraine demonstrate how vulnerable our food security and supply chains are,” he said.

“We need to be prepared and Murdoch can play an important role in this through our agricultural research.

“If I look at where we want to be in the next few years, I would like to contribute to establishing Murdoch University as a centre of excellence in agricultural genomics and biotechnology, delivering our translational research to industry in Australia and doing the research that will contribute to food security to Africa and Asia.

“That’s the dream and that’s what I am working toward with my Murdoch colleagues and through continued collaborations worldwide.”

Professor Varshney is Director of both the State Agricultural Biotechnology Centre and Centre for Crop and Food Innovation in the Food Futures Institute.